Fine Arts Library closed for the summer

The Fiske Kimball Fine Arts Library will be closed from May 19 to Aug. 15 due to construction on the patio surrounding the building.

Other Library locations will remain open. To find group or study spaces in other Library locations, visit library.virginia.edu/hours. During the closure, Fine Arts materials can be requested in Virgo for delivery to another Library location, and summer course reserves will be available in Clemons Library.

The nearby book drop boxes will also be closed during this time. Open drive-up drop boxes are located at Ivy Stacks and in the Central Grounds Parking Garage and there are a number of walk-up drop boxes elsewhere on Grounds. For directions and maps to all Library locations and drop boxes, visit library.virginia.edu/map.

Questions? Ask a Librarian or contact your subject liaison.

7 Books (and a movie) to celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

Guest post by Haley Gillilan (Undergraduate Student Success Librarian), and Keith Weimer (Librarian for History and Religious Studies).

May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, making it a great time to feature materials created by, for, and about Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Join the Library in celebrating this heritage month and take a look at our recommendations below!

“Saving Time: Discovering A Life Behind the Clock” by Jenny Odell (Random House, 2023)

“Saving Time: Discovering A Life Behind the Clock” by Jenny Odell (Random House, 2023)

In her follow-up to her great work on resisting the attention economy, “How to Do Nothing,” Jenny Odell examines different senses of time. This book is incredibly expansive, considering the history of timekeeping, how we perceive time, and reflecting on how our relationship with time has changed over the pandemic. I found that this book took me quite some time to read, because I was digesting and savoring every page, and making many annotations. Ultimately, I found Odell’s book thought-provoking and emotionally resonant. —Haley Gillilan

“In Waves” by AJ Dungo (Nobrow, 2019)

“In Waves” by AJ Dungo (Nobrow, 2019)

This beautiful graphic novel by AJ Dungo is a meditation on grief and surfing. While it might not seem as if those two concepts naturally mesh, Dungo weaves together a gorgeous and heartbreaking narrative about the loss of his girlfriend, alongside the history of the sport. Elegant, monochromatic, full-page illustrations of water and islands wash over the reader. For those grappling with sadness, depression, or complicated grief, Dungo’s graphic novel might be a soothing balm and reminder that they are not alone. —Haley Gillilan

“The Bandit Queens” by Parini Shroff (Ballantine Books, 2023)

“The Bandit Queens” is unlike anything I’ve ever read. This novel follows a group of women in India who are plotting to get rid of their husbands, but if you think you know where this is going, I assure you that you don’t. I think that this novel would ultimately be considered “women’s fiction,” but it has something for everyone. It’s sadistically funny, tenacious, culturally immersive, and intense, but it also has some cozy mystery elements that many people would love. Anyone looking for an energetic rollercoaster with searing feminist commentary, look no further than Shroff’s “The Bandit Queens.” —Haley Gillilan

“The Bandit Queens” is unlike anything I’ve ever read. This novel follows a group of women in India who are plotting to get rid of their husbands, but if you think you know where this is going, I assure you that you don’t. I think that this novel would ultimately be considered “women’s fiction,” but it has something for everyone. It’s sadistically funny, tenacious, culturally immersive, and intense, but it also has some cozy mystery elements that many people would love. Anyone looking for an energetic rollercoaster with searing feminist commentary, look no further than Shroff’s “The Bandit Queens.” —Haley Gillilan

“Insurrecto” by Gina Apostol (Soho, 2018)

Gina Apostol’s novel “Insurrecto” presents an encounter between a Filipina immigrant, Magsalin (her professional name), and an American filmmaker, Chiara Brasi. Chiara is hoping to finish her father’s film about an uprising against American troops occupying the Philippines after the Spanish-American War, which led to U.S. acquisition of the Philippines, and has hired Magsalin as a translator of and consultant for her script. The novel uses the interactions between the two women, as well as depictions of the uprising and events from the 1970s when both women were children and Chiara’s father was using the Philippines as a set for a film about the Vietnam War, to represent stages in the history of U.S. imperialism and Filipino-American interactions. —Keith Weimer

Gina Apostol’s novel “Insurrecto” presents an encounter between a Filipina immigrant, Magsalin (her professional name), and an American filmmaker, Chiara Brasi. Chiara is hoping to finish her father’s film about an uprising against American troops occupying the Philippines after the Spanish-American War, which led to U.S. acquisition of the Philippines, and has hired Magsalin as a translator of and consultant for her script. The novel uses the interactions between the two women, as well as depictions of the uprising and events from the 1970s when both women were children and Chiara’s father was using the Philippines as a set for a film about the Vietnam War, to represent stages in the history of U.S. imperialism and Filipino-American interactions. —Keith Weimer

“Making A Scene” by Constance Wu (Scribner, 2022)

“Making A Scene” by Constance Wu (Scribner, 2022)

This book of essays by actress Constance Wu is a refreshing memoir, with a mix of some heavy hitting emotional reflections and heartwarming anecdotes. I was looking forward to this book because Constance Wu has been brave and outspoken about abuse in the entertainment industry, and I wanted to read more about her experiences in her own words. I think that readers in our community might be particularly interested in this work, as Wu grew up in Richmond, Virginia, and some of her childhood memories feature prominently in the book. —Haley Gillilan

“Four Great Treasures of the Sky” by Jenny Tinghui Zhang (Flatiron Books, 2022)

“Four Great Treasures of the Sky” by Jenny Tinghui Zhang (Flatiron Books, 2022)

For those looking for a book about characters living in a time period that is rarely depicted in mainstream media, “Four Treasures of the Sky” might have something to teach you. Our heroine, Daiyu, is smuggled from China to the United States in the 1880s. She adapts to her circumstances and fights for her freedom across the American West. Keep a box of tissues nearby, though, as the book barrels towards a heartbreaking conclusion. In Jenny Tinghui Zhang’s author’s note, she mentions that this book was an attempt to tell a story that is lost to time and give a narrative to those affected by the Chinese Exclusion Act. I recommend this book to all lovers of historical fiction.—Haley Gillilan

“After Yang” directed by Kogonada (A24 Films, 2021)

“After Yang” directed by Kogonada (A24 Films, 2021)

A very low-fi science fiction gem, it’s possible that “After Yang” slipped under your radar. Set in a near future where robots are used as nannies, Jake (Colin Farrell) desperately tries to find a fix for his daughter’s adoring and gentle android friend, Yang. In his efforts, he encounters Yang’s life beyond who he was as a babysitter. “After Yang” doesn’t have a lot of flashy special effects or explosions that these types of stories usually come with, but digs deep into existential ideas about grief and contentment. You can stream “After Yang” on our library streaming platform, Swank. —Haley Gillilan

“Christian Pluralism in the United States: The Indian Immigrant Experience” by Raymond Brady Williams (Cambridge University Press, 1996)

Raymond Brady Williams’ scholarly monograph, “Christian Pluralism in the United States: The Indian Immigrant Experience,” provides a through overview of this vibrant segment of the Indian American community circa 1996. Almost every Christian tradition in the American landscape is represented in the Indian community, and these are not all products of imperial missionary endeavors. (The “Mar Thoma Christians” and their “Malabar Rite” Catholic offshoots claim a heritage dating back to Jesus’ disciple Thomas in the first century.) These Christian communities experience many tensions in trying to maintain a faith commitment along with (regional) ethnic and in some cases caste identities, marriage traditions and rituals from the Indian subcontinent. Only the Baptists seem to have built something of a “pan-Indian” identity. A review of Prema Kurien’s 2017 book, “Ethnic Church Meets Megachurch: Indian American Christianity in Motion,” which I haven’t read, suggests that most of these tensions have continued for the past quarter-century, with shifts towards greater Americanization and “nondenominational” Protestantism (trends also present among other American ethnic groups). —Keith Weimer

Raymond Brady Williams’ scholarly monograph, “Christian Pluralism in the United States: The Indian Immigrant Experience,” provides a through overview of this vibrant segment of the Indian American community circa 1996. Almost every Christian tradition in the American landscape is represented in the Indian community, and these are not all products of imperial missionary endeavors. (The “Mar Thoma Christians” and their “Malabar Rite” Catholic offshoots claim a heritage dating back to Jesus’ disciple Thomas in the first century.) These Christian communities experience many tensions in trying to maintain a faith commitment along with (regional) ethnic and in some cases caste identities, marriage traditions and rituals from the Indian subcontinent. Only the Baptists seem to have built something of a “pan-Indian” identity. A review of Prema Kurien’s 2017 book, “Ethnic Church Meets Megachurch: Indian American Christianity in Motion,” which I haven’t read, suggests that most of these tensions have continued for the past quarter-century, with shifts towards greater Americanization and “nondenominational” Protestantism (trends also present among other American ethnic groups). —Keith Weimer

Recommended reading for Jewish American Heritage Month 2023

Guest post by Sherri Brown, UVA Librarian for English and Digital Humanities

Since 2006, the United States has observed Jewish American Heritage Month each May. It may come as no surprise that the University of Virginia Library is celebrating the occasion with a list of recommended books by Jewish authors. See some of our recommendations below, along with picks from students in Professor Caroline Rody’s spring 2023 English class, Contemporary Jewish Fiction. We hope you find a book or two to pique your interest! (Find more events and materials related to Jewish American heritage here.)

Fiction:

“The Latecomer” by Jean Hanff Korelitz (Celadon Books, 2022)

Jean Hanff Korelitz’s novel follows the lives of the Oppenheimers, a family plagued by tragedy and its emotional repercussions. Phoebe, the last of four children, is born to Salo and Johanna 18 years after her triplet siblings. She must navigate the fallout from the web of lies and secrets her parents and the triplets have created over the years in order to understand the past and bring peace to her family. An engaging read that elicits a reflection on what it is that binds a family together and whether sharing a bloodline is not enough.

Jean Hanff Korelitz’s novel follows the lives of the Oppenheimers, a family plagued by tragedy and its emotional repercussions. Phoebe, the last of four children, is born to Salo and Johanna 18 years after her triplet siblings. She must navigate the fallout from the web of lies and secrets her parents and the triplets have created over the years in order to understand the past and bring peace to her family. An engaging read that elicits a reflection on what it is that binds a family together and whether sharing a bloodline is not enough.

– Recommended by Sherri Brown, Librarian for English and Digital Humanities

“The Chosen” by Chaim Potok (Simon & Schuster, 1967)

Set in 1940s-era Brooklyn, Chaim Potok’s 1967 novel “The Chosen” paints a vivid and unstable world through the eyes of adolescent Reuven Malter, a young, modern Orthodox Jew who longs to become a rabbi. After a dramatic encounter on a baseball field, Reuven eventually strikes up a friendship with a young Hasid named Danny, the son of the larger-than-life rabbinic sage and tzaddik/leader, Reb Saunders. Though they hail from extremely different backgrounds, the boys rely on each other to navigate their entrance into adulthood.

Set in 1940s-era Brooklyn, Chaim Potok’s 1967 novel “The Chosen” paints a vivid and unstable world through the eyes of adolescent Reuven Malter, a young, modern Orthodox Jew who longs to become a rabbi. After a dramatic encounter on a baseball field, Reuven eventually strikes up a friendship with a young Hasid named Danny, the son of the larger-than-life rabbinic sage and tzaddik/leader, Reb Saunders. Though they hail from extremely different backgrounds, the boys rely on each other to navigate their entrance into adulthood.

Potok has crafted a masterful work rich with characterization and cultural depth. He captures the classic essence of a coming-of-age story and raises questions about Jewishness and the life-altering influence of friendship. Once Reuven and Danny’s paths intertwine, their life trajectories take on a new definition, and nothing will ever be the same.

— Recommended by Caroline Ford, graduate student

Beatrice White, an undergraduate student in Professor Rody’s class, also recommended “The Chosen,” explaining that “each page is a delicacy, detailing the beautiful and troubling journey from Jewish boyhood to manhood,” and describing the novel as “a must-read for any interested in the intricacies of young Jewishness and just how powerful friendship can be.”

“The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick (1980). Printed in book format by Knopf, 1989.

I highly recommend “The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick as an important piece of Holocaust literature. It is a harrowing short story about three characters, Rosa, Magda, and Stella, on their march to a concentration camp. During this march, Rosa tries in vain to keep her infant daughter, Magda, hidden from Nazi officers. She does this by concealing her in a shawl, which she keeps close to her breast. Throughout the story, this shawl acts as a layer of protection between Magda and the horrors of the outside world.

I highly recommend “The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick as an important piece of Holocaust literature. It is a harrowing short story about three characters, Rosa, Magda, and Stella, on their march to a concentration camp. During this march, Rosa tries in vain to keep her infant daughter, Magda, hidden from Nazi officers. She does this by concealing her in a shawl, which she keeps close to her breast. Throughout the story, this shawl acts as a layer of protection between Magda and the horrors of the outside world.

The reason why this story resonated so much with me is because it deals with themes of motherhood. There are many things about the Holocaust that are horrifying, but probably the most gut-wrenching to me is the sheer number of families that were torn apart. Although this short story is technically a work of historical fiction, Ozick has stated that the events in the story are an amalgamation of testimonies she heard from women who lost their children at concentration camps. Ozick does an incredible job of illustrating this inhumanity in an almost surreal way. Her writing is filled with unusual metaphors and bizarre analogies, ones that make the horrifying events in the story difficult to digest — but at the same time, you as a reader are unable to look away from the page. This is emblematic of how the protagonist, Rosa, feels on the inside, because after all, it must be impossible for her to fully comprehend the inhumanity that she is experiencing all around her. By the end of the story, the reader feels just as heartbroken as she does.

– Recommended by Leilani Johnson, undergraduate student

“Her First American” by Lore Segal (Knopf, 1985)

Lore Segal’s “Her First American” tells the semi-autobiographical story of the relationship between Ilka Weissnix, a young Jewish refugee from Nazi Europe, and Carter Bayoux, an older Black American. Carter is a teacher, and he makes it his mission to teach Ilka how to become naturalized into America’s unique racial culture. Through his lessons and Ilka’s experiences, readers watch people from different backgrounds fight to achieve coexistence in a divided world that works against them. Themes of empathy saturate the plot while Carter struggles with alcoholism and Ilka must learn how to relate to her traumatized mother. In this character-driven novel, Segal asks questions about how social conformity creates constrictions on relationships — and how people can overcome those restrictions.

Lore Segal’s “Her First American” tells the semi-autobiographical story of the relationship between Ilka Weissnix, a young Jewish refugee from Nazi Europe, and Carter Bayoux, an older Black American. Carter is a teacher, and he makes it his mission to teach Ilka how to become naturalized into America’s unique racial culture. Through his lessons and Ilka’s experiences, readers watch people from different backgrounds fight to achieve coexistence in a divided world that works against them. Themes of empathy saturate the plot while Carter struggles with alcoholism and Ilka must learn how to relate to her traumatized mother. In this character-driven novel, Segal asks questions about how social conformity creates constrictions on relationships — and how people can overcome those restrictions.

– Recommended by an undergraduate student

“Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman (Pantheon Books, 1986)

When it comes to modern Jewish literature, specifically Holocaust literature, the book I think best encapsulates this genre is the graphic novel “Maus” by Art Spiegelman. What stands out about “Maus” is how it depicts multiple generations of post-Holocaust trauma, and the reader can get the full scope of the impact of the event. Through the father’s story, the reader can learn about the history of the Holocaust, including the rise of the Nazi party and the experience of the concentration camps. Then, through the son’s narrative, the reader can gain insight into the prolonged impact of the Holocaust on the family dynamic. The father’s struggles with money and love show the long-term trauma of the Holocaust. The reader can also better understand second-generation Holocaust trauma through the son’s struggles with his father’s experiences. With “Maus,” readers can better understand the true impact of the Holocaust on American Jewish families, while also reading a compelling historical novel.

When it comes to modern Jewish literature, specifically Holocaust literature, the book I think best encapsulates this genre is the graphic novel “Maus” by Art Spiegelman. What stands out about “Maus” is how it depicts multiple generations of post-Holocaust trauma, and the reader can get the full scope of the impact of the event. Through the father’s story, the reader can learn about the history of the Holocaust, including the rise of the Nazi party and the experience of the concentration camps. Then, through the son’s narrative, the reader can gain insight into the prolonged impact of the Holocaust on the family dynamic. The father’s struggles with money and love show the long-term trauma of the Holocaust. The reader can also better understand second-generation Holocaust trauma through the son’s struggles with his father’s experiences. With “Maus,” readers can better understand the true impact of the Holocaust on American Jewish families, while also reading a compelling historical novel.

– Recommended by Grace Theriot, undergraduate student

“Jewish Humor” section of “Jewish American Literature: a Norton Anthology” edited by Jules Chametzky, John Felstiner, Hilene Flanzbaum, and Kathryn Hellerstein (W.W. Norton, 2001)

Jewish comedy defies easy explanation. Perceptive critics have described any attempts to identify a distinctively Jewish sense of humor as fruitless since, for any claim made as to what it truly is, a little thought immediately uncovers all kinds of exceptions and counterexamples. Furthermore, the counterexamples themselves go beyond being merely illustrative; they are nearly as extensive and numerous as Jewish history, which spans a wide geographic area, literally and figuratively. The book offers many examples showcasing alternative takes in a humorous way, leaving readers in awe. The recurrence of dark comedy in the book may particularly capture readers. I highly recommend this work, as readers will dive into a whole world of stories in different settings that will keep them on their toes.

Jewish comedy defies easy explanation. Perceptive critics have described any attempts to identify a distinctively Jewish sense of humor as fruitless since, for any claim made as to what it truly is, a little thought immediately uncovers all kinds of exceptions and counterexamples. Furthermore, the counterexamples themselves go beyond being merely illustrative; they are nearly as extensive and numerous as Jewish history, which spans a wide geographic area, literally and figuratively. The book offers many examples showcasing alternative takes in a humorous way, leaving readers in awe. The recurrence of dark comedy in the book may particularly capture readers. I highly recommend this work, as readers will dive into a whole world of stories in different settings that will keep them on their toes.

– Recommended by Sultana Omar, undergraduate student

Nonfiction:

“Voices From Shanghai: Jewish Exiles in Wartime China” edited, translated, & with an introduction by Irene Eber (University of Chicago Press, 2008). Also available as an ebook.

In the years leading up to the Second World War, many Jewish families fled Germany, Poland, and surrounding countries. A sizeable contingent of Jewish refugees — between 18,000 and 20,000 — arrived in Shanghai, China, between 1938 and 1941 (according to Eber), joining the over 6,000 Russian Jews who had arrived earlier in the 1930s. Eber brings us first-hand accounts of life in Shanghai before, during, and after the war through translated poems, stories, letters, and diaries penned by Jewish refugees during that time. While many of the Jews in Shanghai eventually immigrated to the United States, Canada, Australia, and other locales, this book is an important contribution to providing a glimpse of the range of feelings and experiences had by Jewish refugees during their time in China.

In the years leading up to the Second World War, many Jewish families fled Germany, Poland, and surrounding countries. A sizeable contingent of Jewish refugees — between 18,000 and 20,000 — arrived in Shanghai, China, between 1938 and 1941 (according to Eber), joining the over 6,000 Russian Jews who had arrived earlier in the 1930s. Eber brings us first-hand accounts of life in Shanghai before, during, and after the war through translated poems, stories, letters, and diaries penned by Jewish refugees during that time. While many of the Jews in Shanghai eventually immigrated to the United States, Canada, Australia, and other locales, this book is an important contribution to providing a glimpse of the range of feelings and experiences had by Jewish refugees during their time in China.

– Recommended by Sherri Brown

“Strange Haven: A Jewish Childhood in Wartime Shanghai” by Sigmund Tobias (University of Illinois Press, 1999)

For a more detailed account of day-to-day life in Shanghai during WWII, consider this memoir by Sigmund Tobias, Eminent Research Professor of Educational & Counseling Psychology at the University of Albany. Born in 1932, Tobias was only six years old when he fled from Germany to Shanghai with his parents. Tobias recounts his childhood growing up in Shanghai during the war, as his family and many other Jewish refugees acclimated to a new climate and customs while struggling with poverty, food shortages, and the eventual movement of refugees to a ghetto in part of the Hongkew district. In describing his life, Tobias also expounds on the details of living as an Orthodox Jew in a foreign city. Tobias immigrated to the United States in August of 1948. The final chapters of his memoir tell of his return to Shanghai 40 years after his departure. An illuminating and compelling read.

For a more detailed account of day-to-day life in Shanghai during WWII, consider this memoir by Sigmund Tobias, Eminent Research Professor of Educational & Counseling Psychology at the University of Albany. Born in 1932, Tobias was only six years old when he fled from Germany to Shanghai with his parents. Tobias recounts his childhood growing up in Shanghai during the war, as his family and many other Jewish refugees acclimated to a new climate and customs while struggling with poverty, food shortages, and the eventual movement of refugees to a ghetto in part of the Hongkew district. In describing his life, Tobias also expounds on the details of living as an Orthodox Jew in a foreign city. Tobias immigrated to the United States in August of 1948. The final chapters of his memoir tell of his return to Shanghai 40 years after his departure. An illuminating and compelling read.

– Recommended by Sherri Brown

Researchers can direct queries about Jewish and Jewish American literature to Sherri Brown and research questions regarding Jewish Studies to Miguel Valladares-Llata, Librarian for Romance Languages and Latin American Studies, whose subject specialties include French, German, Jewish Studies, Latin American Studies, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese.

A closer look: Alumni explore Bolívar Collection during ‘Juntos’ weekend

Earlier this month in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, a happy group of alumni, students, and staff posed in front of a portrait of Fernando Bolívar, who was likely the first Latin American student at the University of Virginia. The nephew and adopted son of the Venezuelan leader Simón Bolívar, Fernando enrolled at the University in 1827. He is the namesake for important hubs in UVA’s Latinx community today, including the student residence Casa Bolívar and the Bolívar Network, an alumni steering committee.

The group was gathered for the UVA Alumni Association’s inaugural Juntos weekend, a celebration for Latinx alumni. (The Spanish word “juntos” translates to “together” in English.) As part of that weekend, UVA Library sponsored two events on April 15, including a presentation of Simón and Fernando Bolívar’s artifacts held in Special Collections. For that event, called “A Closer Look: The Bolívar Collection,” UVA Library curators and archivists displayed Simón Bolívar’s silver and manuscripts, Fernando Bolívar’s papers, and portraits of both men that were donated to UVA in 1944 by the Venezuelan government. They also presented more modern items related to the Latinx experience at UVA and the Bolívar Network’s founding.

“The team that interpreted the objects from the Library’s Bolívar family collection were so thoughtful in their explanations and care for the precious items and their stories,” said attendee Gina Flores, a 2000 UVA alumna and founding student member of the Bolívar Network. “I appreciated the 1827 Bolívar history paired with more current Latinx histories. Seeing some of the founding documents of the Bolívar Network from decades ago reminded me how important it is to collect and preserve UVA Latinx history, past, present, and future. Seeing our community’s history validated my connection to UVA and sense of belonging as an alumna.”

That same morning, the Library partnered with Microsoft’s HOLA Network (its internal Latinx employee resource group), to host a breakfast in Special Collections’ Harrison-Small Auditorium, where Latinx Microsoft employees shared video testimonials about the power of Latinx community. “A weekend like this one is an opportunity for units, schools, and groups across the University to reflect on the journey of Latinx students, faculty and staff since the University’s founding,” said Catalina Piatt-Esguerra, the Library’s Associate Dean of Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility, during the Microsoft event. “It’s a weekend that reminds us of the impact of community and the power of representation.”

Take a look below at images from that day, captured by photographer and Library employee Eze Amos.

For more about the Bolívar Collection, check out these links in the Library catalog:

- Fernando Simón Bolívar papers (MSS 12214)

- Papers pertaining to Fernando Simón Bolívar (MSS 38-205)

- Bolívar Family Silverware (MSS 14121)

Introducing the Iselin Collection of Humor

The University of Virginia Library is delighted to announce the donation of a major gift, the Iselin Collection of Humor. Built over many years by noted collector and retired attorney Josephine Lea Iselin, the Iselin Collection will be a tremendous asset for research and learning at the University across a wide range of disciplines.

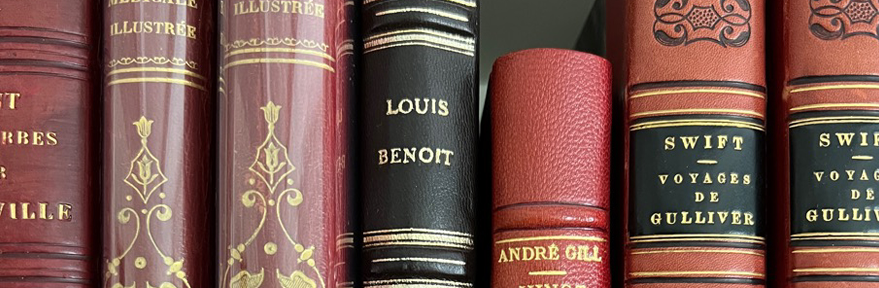

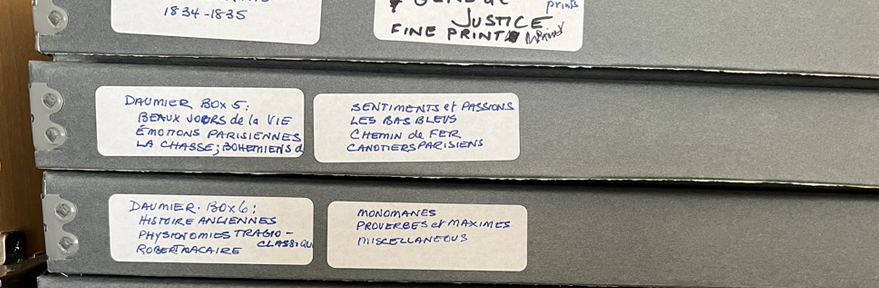

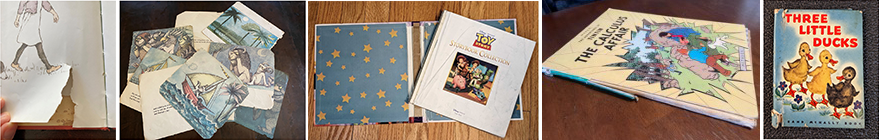

The Iselin Collection, which will reside in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, consists of illustrated books, reference materials, periodicals, prints, manuscripts, and ephemera, principally of social and political satire. The Iselin Collection encompasses more than 800 items, including significant works of 19th-century English and French material, a 20th-century collection of illustrated humor books by well-known editorial cartoonists of the era, and an adjunct collection of 19th- and 20th-century American illustrated fiction, put together, as Iselin noted, “with an emphasis on the quality of the illustration and pure whimsy.”

Both the English and French materials include works by the most celebrated graphic humorists of the period. Giants of the genre of satire and caricature, such as George and Robert Cruikshank in England and Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, and J.J. Grandville in France, are the focus of the collections, but many other artists are included. Charles H. Bennett, Richard Doyle, Alfred Henry Forrester, Harold Knight Browne (Phiz), Thomas Rowlandson, John Tenniel, Charles Amédée de Noé (Cham), André Gill, Rodolphe Töpffer, and dozens of other well-known illustrators all appear. Portions of the collection have been the subjects of recent exhibitions at the Grolier Club (in New York City, where Iselin resides). In 2017, the club displayed “Vive les Satiristes! French Caricature during the Reign of Louis Philippe, 1830-1848,”, followed by “The Great George: Cruikshank and London's Graphic Humorists, 1800-1850” in 2021. “Vive les Satiristes!” and “The Great George” were curated by Iselin, and catalogs were published for both exhibitions.

The Iselin Collection has far-ranging potential for research, instruction, exhibition, and outreach, as the items relate to many fields of study, including art, art history, literature, political science, history, and media studies. In addition to availability in the Small Special Collections Library, the collection will also be used in Rare Book School courses in illustration, printing, bibliography, book arts, and book history.

Brenda Gunn, Associate University Librarian for Special Collections and Preservation, noted the importance of the collection. “Not only will it vastly improve our 19th-century French and English holdings, but it also serves as a complement and connection to our materials in American political cartooning and satire,” she said. The Library has significant holdings in that area, including manuscript collections, materials in the Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History, and the papers of acclaimed political cartoonist Patrick Oliphant, whose archive the University acquired in 2018.

Gunn remarked upon another distinction of the collection. “The Iselin Collection is notable not just for its exceptional content but also as one of the few gatherings of rare materials at the Library amassed by a female collector. The collection reflects Lea Iselin’s critical eye and her passion for the materials, and it shows her extraordinary skill in assembling them into a unified whole. Finally, the collection is in excellent overall condition. We are grateful to her for this singular gift and look forward to stewarding it and making it available for scholars and visitors.”

The Iselin Collection of Humor is currently being cataloged. The UVA Library will continue to highlight this important collection as work proceeds.

Have a book in need of repair? Check out the Community Book Clinic!

Sue Donovan was raised in Middle Tennessee, where her mother was a storyteller and worked at the county library. “We basically grew up in the library. I brought books to school to read behind the books that we were supposed to read in class,” she said. Now as Conservator for Special Collections at the University of Virginia Library, Donovan still spends her days surrounded by books, mending torn pages and repairing broken bindings. Later this month, she is offering her services to the local community, in partnership with the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library (which was named the Virginia Library Association’s 2022 Library of the Year).

In honor of Preservation Week, UVA Library and JMRL will host a Community Book Clinic from April 30 to May 6. If you have a book in need of repair, drop it off at your local JMRL branch in Charlottesville or Albemarle, Greene, Louisa and Nelson counties. Place your book in a reusable bag with a completed waiver (there is a one-book limit per family). Donovan, with a team of six additional UVA Library staff members, will mend rips and tears, sew in detached pages, and fix damaged bindings and spines, all for no cost. The repaired books will be ready for pickup in June. “Ever since I moved here [in 2016], I've wanted to do something like this,” Donovan said. “I love being able to help members of the community and local organizations who don’t have conservators on staff.”

Donovan, who studied book conservation at the Sorbonne in Paris, mends tears using traditional Japanese methods. “We use paper made out of the mulberry plant … and we apply that with a wheat starch paste,” she said. “It’s kind of like tape, but inherently removable with the same solvent, which is water.” While this method of repair is time consuming (the mended pages must be dried under weights until the water evaporates), the mend holds firmly in place once dry, and can be removed with water at any time without further damaging the book.

Book conservators consider adhesive tape to be “evil,” Donovan said with a laugh, because tape can solubilize ink and pigments. “If you put a piece of Scotch tape down on top of a family letter that was written in ballpoint pen, the ink can go up into the adhesive. And even if you remove the tape, which is possible to do, you have damaged part of your heritage.” The Community Book Clinic cannot remove tape from books at this time, as the library that includes the Conservation Lab is under renovation. “We need a fume hood to extract the solvent vapors. So we just can't deal with tape removal for this particular book clinic,” Donovan said.

The clinic can accept up to 75 books total to repair this year. “We’re starting slow, but I’m hoping that the clinic will be a yearly event going forward,” Donovan said. Below, read a few of Donovan’s recommendations for preserving your favorite books at home:

- Rule number one is don’t tape your pages, unless, say, you have to carry your book on a journey, and you don’t have any other way to keep the pages intact.

- Keep things out of direct sunlight; ultraviolet light can really damage leather, damage cloth, damage paper.

- Don’t keep books in the basement or the attic or any other place that doesn’t have temperature control.

- If there are loose pages, or parts of the book are falling off, there are websites out there where you can custom order an archival box and save the materials for your descendants.

The Community Book Clinic begins April 30 and runs through May 6. Visit our Preservation Services page for additional information about caring for your personal book collection.

Join us for a special event: “Keep the Music Playing!”

The UVA Library welcomes members of the Charlottesville community to celebrate eighty years of Music Department history!

Join us at 2 p.m. on Wednesday, April 26, for celebration and performances reflecting on musical recordings dating as far back as the 1940s. The celebration marks completion of a digitization project, making these recordings available for years to come. The event will take place in the auditorium of Harrison/Small; doors open at 1:30.

The event is free and open to the public, and refreshments will be served. It is presented by the University of Virginia Library and sponsored by the UVA Arts Council.

Amy Hunsaker, Librarian for Music & the Performing Arts, elaborates on the project:

The UVA Music Department has been recording their performances for the better part of eighty years. UVA librarians have actively collected, cataloged, and preserved Music Department recordings as part of the circulating collection. Many Music Department and Library staff put their hearts into making sure these recordings would remain available to future listeners. However, it was made clear during the pandemic that we needed to create a new process to collect and archive the performances so they would be better protected. With this in mind, I worked with University Archivist Lauren Longwell to seek an Arts Council grant which we called, “Keep the Music Playing.” The funds were in part used to pay a project intern to process the existing collection into the University Archives and create a new workflow to collect existing and future recordings.

We will be celebrating the culmination of this project at the April 26 event, where attendees will be able to interact with the collection. Celebrated composer Judith Shatin will speak and we will be treated to a live performance by the Glee Club. The event is supported by the UVA Arts Council.

We wanted to provide a unique view of the collection, so we asked our project intern, UVA fourth-year student Emma Radcliff, to reflect on her experience as a student interacting with many decades of musical UVA history. Emma writes:

After nine months of work, the “Keep the Music Playing” archival project is finally nearing its completion. In total, we inventoried 3,401 items, and processed 522 more. We sorted 2,430 CDs, 466 DATs, 482 cassettes, and a plethora of digital files, reel-to-reels, and concert programs. This collection deserved every moment we spent on it.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of this project. With materials hailing from as early as the 1940s, the collection represents a deeply significant slice of the University’s history, and as such serves as a lens through which to view enormous historical landmarks — not only has music itself developed over the past near-century with the adoption of digital creation, advanced recording technologies, and new performance styles, but the diversification of the University has profoundly enriched its musical culture. The sheer breadth of this collection — which features Afropop, pipa recitals, jazz, women’s groups, experimental noise, folk music, opera, and so very much more — is demonstrative of a community which expresses its heterogeneous identities in a way that joins people through artistic experience. It’s a trend that I hope will continue.

Given its significance, the collection needed to be organized for preservation and public access. Accessibility is, of course, at the root of archival practice, and this one has been inventoried at the item level, which is often not possible for large collections. That means that every item with a record is searchable, and every item that lacked a record is still organized to enable discovery by researchers, curious students, or alumni who want to find their old performances.

Working on this collection has been fulfilling. It’s been a challenge, to be sure — working with eighty years’ worth of material means encountering different cataloging styles, parsing impossible handwriting from the 1970s, and wondering why a series of chronologically-ordered cassette tapes from 1996 were labeled “1,” “2,” and then… “B.” I owe thanks to Winston Barham, who put an incredible amount of personal effort into recording, labeling, and cataloging many of the records between 2004 and 2020 before this project was even a glimmer in an archivist’s eye. His hard work, along with that of student employees, contributed hundreds of performance recordings to the collection and enabled me to identify items quickly, which is why so many records could be inventoried at the item level.

I am grateful too for the support of the UVA Arts Council, who recognized the importance of this collection and offered us the resources to properly process it. Their contribution made this possible.

--

The “Keep the Music Playing” collection will be shelved at Ivy Stacks, and will be searchable through an ArchiveSpace finding aid later in 2023. We hope that you have the opportunity to explore it; it is a treasure of the University.

Access Wall Street Journal (new!) and New York Times through UVA Library

The Library is now offering access to the Wall Street Journal, including daily news reporting and coverage from around the world.

To access, visit https://wsj.com/uva. You will be prompted to create an account, which you can then use on wsj.com, the Wall Street Journal app, and the Wall Street Journal archives.

With the highest print circulation in the United States, the Wall Street Journal is available in English, Chinese, and Japanese, and users can view the online and print versions through wsj.com. The print edition of the Journal has been available continuously since its launch in 1889, and the paper has won 38 Pulitzer Prizes.

In addition to the Wall Street Journal, Library users can…

- Read the New York Times online: Learn how to create your free New York Times account.

- Browse a large number of contemporary papers through Factiva.

- Access more than 50 newspaper databases, including historical newspapers. Many of these are also discoverable in Virgo.

Accounts are available to active students, faculty, and staff using a virginia.edu email account.

5 Books for Arab American Heritage Month

Did you know that Virginia recognized April as Arab American Heritage Month long before it became a national designation in 2022? You can help celebrate the many cultures represented by Arab Americans by exploring the wealth of literature and poetry held by the University of Virginia Library. We’ve enlisted the efforts of UVA graduate students Gretchen Masse and Katelyn Eschmann and librarians Leigh Rockey and Amy Hunsaker. All are avid readers who are excited to share their reviews of old favorites and new discoveries.

“A Woman is No Man,” a New York Times bestseller, is Palestinian-American author Etaf Rum’s first novel. It moves in and out of the past and present as it beautifully interweaves the story of Isra, a young Palestinian woman who moves to New York for an arranged marriage, and her daughter Dreya. Dreya is now a teenager seeking to recover the truth of the untimely death of her parents. As Dreya faces the prospect of an arranged marriage, she grapples with her own ambitions for an independent identity and the expectations and needs of her family — similar to her mother’s journey. Rum highlights the mother/daughter bond while also uncovering the traumatic danger of family secrets. “A Woman is No Man” is a moving, challenging read for all interested in a woman’s right to self-determination and freedom, and the specific nature that journey takes when a woman must navigate both a new, foreign culture and traditional, patriarchal customs. (Katelyn Eschmann)

“A Woman is No Man,” a New York Times bestseller, is Palestinian-American author Etaf Rum’s first novel. It moves in and out of the past and present as it beautifully interweaves the story of Isra, a young Palestinian woman who moves to New York for an arranged marriage, and her daughter Dreya. Dreya is now a teenager seeking to recover the truth of the untimely death of her parents. As Dreya faces the prospect of an arranged marriage, she grapples with her own ambitions for an independent identity and the expectations and needs of her family — similar to her mother’s journey. Rum highlights the mother/daughter bond while also uncovering the traumatic danger of family secrets. “A Woman is No Man” is a moving, challenging read for all interested in a woman’s right to self-determination and freedom, and the specific nature that journey takes when a woman must navigate both a new, foreign culture and traditional, patriarchal customs. (Katelyn Eschmann)

“The Arsonists’ City” by Hala Alyan is one family’s story written across Brooklyn, Damascus, Beirut, Austin, and a small California town called Blythe. Of course, these locations function as characters, but they never distract from the engaging and sometimes enraging ancestral drama. You get to know each member of the family well, going inside everyone’s story while they struggle with secrets and gather for what might be the last time at the family homestead in Lebanon. This novel is Alyan’s second, following the amazing “Salt Houses,” and it’s worth everyone’s time. (Leigh Rockey)

“The Arsonists’ City” by Hala Alyan is one family’s story written across Brooklyn, Damascus, Beirut, Austin, and a small California town called Blythe. Of course, these locations function as characters, but they never distract from the engaging and sometimes enraging ancestral drama. You get to know each member of the family well, going inside everyone’s story while they struggle with secrets and gather for what might be the last time at the family homestead in Lebanon. This novel is Alyan’s second, following the amazing “Salt Houses,” and it’s worth everyone’s time. (Leigh Rockey)

In “Esther’s Notebooks: Tales from My 10-Year-Old Life,” Riad Sattouf, author of the memoir “The Arab of the Future,” based his main character Esther on his daughter’s friend. Every week he would chat with her and from those conversations grew a comic series. Each of the 54 pages of this graphic novel is a self-contained story about a week in the life of its protagonist. This is the first book in a series that stretches four more years to a 14-year-old Esther in France. Esther is eminently relatable and Sattouf’s writing is a highlight of the Arab diaspora. (Gretchen Massey)

In “Esther’s Notebooks: Tales from My 10-Year-Old Life,” Riad Sattouf, author of the memoir “The Arab of the Future,” based his main character Esther on his daughter’s friend. Every week he would chat with her and from those conversations grew a comic series. Each of the 54 pages of this graphic novel is a self-contained story about a week in the life of its protagonist. This is the first book in a series that stretches four more years to a 14-year-old Esther in France. Esther is eminently relatable and Sattouf’s writing is a highlight of the Arab diaspora. (Gretchen Massey)

Laila Lalami is one of my favorite Arab American authors, but before this year, I had never read her brilliant fictional memoir, “The Moor’s Account,” which was a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction finalist in 2015. The story is based on true characters who were involved with the disastrous Narváez expedition that began in Florida in 1527. Our narrator and protagonist is the Moroccan slave Mustafa (called Estebanico by the Spanish), considered to be the first Black explorer of the Americas. Lalami’s use of language allows the reader to view the events from the perspective of a 16th-century Muslim man who is forced to participate in the Spanish invasion of indigenous American settlements and left to survive in a brutal wilderness after the expedition fails. The real events of the story took place over the span of a decade, but the narrative propels the reader forward so that it is nearly impossible to put the book down, even if it’s 1:30 a.m. and the reader needs to work in the morning. (Amy Hunsaker)

Laila Lalami is one of my favorite Arab American authors, but before this year, I had never read her brilliant fictional memoir, “The Moor’s Account,” which was a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction finalist in 2015. The story is based on true characters who were involved with the disastrous Narváez expedition that began in Florida in 1527. Our narrator and protagonist is the Moroccan slave Mustafa (called Estebanico by the Spanish), considered to be the first Black explorer of the Americas. Lalami’s use of language allows the reader to view the events from the perspective of a 16th-century Muslim man who is forced to participate in the Spanish invasion of indigenous American settlements and left to survive in a brutal wilderness after the expedition fails. The real events of the story took place over the span of a decade, but the narrative propels the reader forward so that it is nearly impossible to put the book down, even if it’s 1:30 a.m. and the reader needs to work in the morning. (Amy Hunsaker)

You can make jokes about 1980s pop hits, but the protagonist of Zaina Arafat’s “You Exist Too Much” is, in fact, addicted to love. This addiction is very real, and it’s ruining her life. Why is it happening? What do her formative gender experiences in Palestine have to do with her current troubles? The interplay of her relationships and her obsessions degrades her lived experience until she seeks treatment and works to find healthy connections with her lovers. Meanwhile, the reader careens around life with her, hoping that meaningful bonds will form out one of her affairs, as long as it’s not that total loser Matias, please. (Leigh Rockey)

You can make jokes about 1980s pop hits, but the protagonist of Zaina Arafat’s “You Exist Too Much” is, in fact, addicted to love. This addiction is very real, and it’s ruining her life. Why is it happening? What do her formative gender experiences in Palestine have to do with her current troubles? The interplay of her relationships and her obsessions degrades her lived experience until she seeks treatment and works to find healthy connections with her lovers. Meanwhile, the reader careens around life with her, hoping that meaningful bonds will form out one of her affairs, as long as it’s not that total loser Matias, please. (Leigh Rockey)

Want to explore more? Here are some great resources to learn more about Arab American issues, literature, and culture:

- Arab American National Museum: https://arabamericanmuseum.org/

- Arab America: https://www.arabamerica.com/

- Arab American Institute: https://www.aaiusa.org/

‘Literature in Context’ seeks to provide a digital alternative to print anthologies. A new NEH grant will help.

Six years ago, University of Virginia English professor John O’Brien and his colleague Tonya Howe, a professor of literature at Marymount University, were both wrestling with a problem in their classrooms. Students, up against rising textbook costs, were coming to class with free, but unvetted versions of assigned reading. “These digital versions of literary texts were poorly edited and annotated — if they were edited at all,” Howe said.

The two professors joined forces with the University of Virginia Library to create “Literature in Context: An Open Anthology of Literature,” a rigorously edited, curated anthology of digital texts that also serves as an open educational resource — students and teachers can access it anywhere for free. Launched in 2017, the project currently offers a vast selection of texts from the 18th century, the period in which both professors specialize. Earlier this year, the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded “Literature in Context” a grant totaling $303,104 to expand the project.

“Our goal is to really scale up Literature in Context to create a full anthology’s worth of texts, from medieval to right up to the copyright line [1927 in the United States],” said Chris Ruotolo, Director of Research in the Arts and Humanities at UVA Library and co-principal investigator of the NEH grant (along with Howe and O’Brien). “Soon, Literature in Context will be usable in lieu of a print anthology that you would typically use for a literature class,” Ruotolo said.

We spoke to Ruotolo, Howe, and O’Brien to learn a bit more about the history and future of Literature in Context.

Q. Can you talk about some of the challenges students are facing when it comes to textbook costs?

Howe: Print anthologies are expensive and also wasteful: most classes use a fraction of these enormous books. Publishers make those anthologies obsolete every few years by coming out with new editions.

O’Brien: And given the cost of textbooks in general, it is not surprising that students often turn to the web and use whatever text comes up first in a search. But they have no way of knowing how to choose a good text from a bad one.

Ruotolo: Students have become very resourceful about finding free versions of these texts. But the versions that they’re getting are not vetted. They’re from different editions, they have errors, they don’t have the same pagination. Teaching to a class where every student has a different version of the text that they’re scrolling through is challenging. Ideally, you want to be teaching with a version of a text that’s authoritative, but at the very least, you want to be teaching with the same version.

Take Shakespeare: there are major, major differences between the earliest editions and later editions. We need to all be working, literally, from the same page, in order to be able to talk about the text in a meaningful way.

Q. Tell me about the early days of Literature in Context and how the project is growing.

O’Brien: The digital texts that students were discovering on their own were bad, but we knew that it was possible to make excellent digital texts, with fuller annotations than any print edition can have, along with images, links to other texts, the ability for students to highlight and interact with the text, and more.

Howe: We began working with students and colleagues to create a digital “anthology” of reliable literary texts that teachers and students can turn to with confidence. We wanted to make it an open educational resource, freely available for classroom use.

Ruotolo: In 2017, John, Tonya, and I received a grant from the NEH to develop a proof of concept, which became Literature in Context. [In full, the project has received three grants — two from the NEH and one from the Virtual Library of Virginia — totaling around $400,000.] Other UVA Library staff have made important contributions to the project. Kristin Jensen was named in the new grant as Project Manager. David Hennigan has supported the project since it first launched, assisting with grant administration and budgeting. Dave Goldstein in Library IT has established and maintained the web hosting environment.

As we were developing Literature in Context, John and Tonya were both using it to teach, so most of the texts in the project are from the 18th century. For many of today’s college students, there are a lot of unfamiliar names, references, and allusions to other literary works in these texts. So, the students were able to dive in, identify the things that are unfamiliar to them that are likely to be unfamiliar to their peers as well.

Q. So, students participate in the making of Literature in Context?

Ruotolo: Yes! Students provide annotations for the text and sometimes ancillary materials like images, and even video clips to help explain some of the details of texts that might be unfamiliar. They also do some of the back-end work of encoding those texts and putting them online. The idea is that every cohort of students who use these texts are creating some research that grows the project that is then used by future cohorts of students.

We also wanted to develop a platform that’s expandable so that down the road, other instructors can add the texts that they use for their classes and continue to grow this body of materials that otherwise we’d be paying publishers for.

O’Brien: We want students, together with faculty, to continue to create annotated editions for Literature in Context as a way into information literacy and the digital humanities.

Q. What are some of your favorite elements of the project? Favorite titles? Favorite assignments?

Ruotolo: The Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein entry is one of my all-time favorites, and it’s also one of the texts that shows off the best version of Literature in Context that’s up now. It has a lot of really rich annotations, and it can show you what the project is all about.

Howe: In developing the project, we thought a lot about what would benefit faculty in the classroom. Instructors using Literature in Context can customize their own anthologies, selecting the texts they want for coursepacks that can, if they wish, be printed on demand.

Ruotolo: Yes, instructors can customize it. They can include texts that are perhaps outside the canon of texts that are typically included in these anthologies — they can include more women authors, more authors of color, more works that were underrepresented or overlooked by previous anthology editors. Literature in Context is infinitely expandable; there’s no limit on page count. So the idea is to have enough text in the hopper that an instructor can go through and pick which texts they want to use in a coursepack.

Q. Can you talk about the ways the project intersects with the open educational resource and digital humanities movements?

Ruotolo: The earliest digital humanities work at UVA Library dates back to the 1990s. Much of this work involved taking digitized texts, indexing them, and making it possible to search across the body of text and look for different words and phrases and compare. Literature in Context really evolves out of that tradition.

I think the inflated cost of print anthologies has been a known issue for a long time. But there is a fair amount of resistance among literature folks to reading on screens, which I think impeded the momentum to move forward with open educational resources in a lot of disciplines.

The COVID pandemic shifted the thinking on that; people were really scrambling to find online texts they could use, and I think it opened up both faculty and student perspectives on how useful digital texts could be. I feel like the time has never been better to really try to get some wider adoption of open education resources for literature classes.

The new NEH grant will allow us to greatly expand the project. And the other piece of the grant is to try to make the texts more easily accessible. This means fine-tuning the accessibility and mobile friendliness, and making texts easily embeddable in course management systems like Canvas, so that it’s that much easier for students to engage with the content. We are really positioning Literature in Context as not just supplementary to what people are teaching, but as a potential replacement for the core course materials.

Browse by category

Browse by date

- November 2018 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- November 2019 (1)

- January 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (2)

- October 2021 (1)

- November 2021 (1)

- January 2022 (4)

- February 2022 (2)

- March 2022 (2)

- April 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (3)

- August 2022 (1)

- September 2022 (2)

- November 2022 (4)

- December 2022 (3)

- January 2023 (6)

- February 2023 (9)

- March 2023 (11)

- April 2023 (6)

- May 2023 (4)

- June 2023 (3)

- July 2023 (1)

- August 2023 (3)

- September 2023 (5)

- October 2023 (7)

- November 2023 (3)

- December 2023 (5)

- January 2024 (4)

- February 2024 (8)

- March 2024 (2)

- April 2024 (6)

- May 2024 (4)

- June 2024 (1)

- July 2024 (2)