Seven books (and a TV show) to celebrate Native American Heritage Month

Guest post from Haley Gillilan (Undergraduate Student Success Librarian) and Keith Weimer (Librarian for History and Religious Studies).

November is Native American Heritage Month! It’s a wonderful opportunity to honor Indigenous traditions, cultures, and histories. At the University of Virginia Library, we’re highlighting work created by and about Native Americans; take a look at staff book and television recommendations below.

Recommended by Leigh Rockey, Video Collections Librarian

“The Removed” by Brandon Hobson (Ecco, 2021)

“The Removed” by Brandon Hobson (Ecco, 2021)

Right from the start in “The Removed,” we know that Ray-Ray, the eldest son of the Echota family, will be killed unjustly by the police. Just a few pages later, we feel like we know him and already mourn the loss of such an endearing character. We work through the grief and anger along with the rest of the family as they each tell their story 15 years after Ray-Ray’s brutal death. Sometimes an ancestor, Tsala, who perished on the Trail of Tears, breaks into the narrative and expands our range of view to encompass Cherokee legends. While the narrative of “The Removed” isn’t bright and sunny, there is a penetrating warmth that leaves the reader full of hope.

Recommended by Meg Kennedy, Curator of Material Culture

“Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes: Nine Indian Writers on the Legacy of the Expedition” edited by Alvin M. Josephy Jr. (Knopf, 2006)

“Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes: Nine Indian Writers on the Legacy of the Expedition” edited by Alvin M. Josephy Jr. (Knopf, 2006)

Inspired by the bicentennial events of the Corps of Discovery, this edited volume of nine essays gives voice to the largely overlooked experiences of the many and distinct Native American sovereign nations affected by the 1803-1806 cross-continent journeys of Lewis and Clark. Readers will be familiar with the colonial stories of exploration: first points of contact, experiences of discovery, the naming of waterways and vast lands, and the emergence of democratic society in a lawless land. The varied essays, though, reframe the narrative, bringing to life long-standing and long-distance trade networks that crossed the continent, long-inhabited lands, long-ago named rivers and places, long-established democratic systems. The authors —leaders and scholars representing diverse tribal communities — use different techniques to address the impacts of the Corps of Discovery, challenging accepted historiographies through their inclusion of oral and shared community records, reconsidered political and economic histories and literary examinations of Manifest Destiny. As author Mark H. Trahant notes, “Eventually other stories surface, too. These alternative histories serve as reminders that the journey continues.”

Recommended by Erin Pappas, Librarian for the Humanities

“There There” by Tommy Orange (Knopf, 2018)

“There There” by Tommy Orange (Knopf, 2018)

Publisher’s summary: A wondrous and shattering novel that follows 12 characters from Native communities, all traveling to the Big Oakland Powwow, all connected to one another in ways they may not yet realize.

Among them are Jacquie Red Feather, newly sober and trying to make it back to the family she left behind; Dene Oxendene, pulling his life together after his uncle’s death and working at the powwow to honor his memory; and 14-year-old Orvil, traveling to perform traditional dance for the very first time. Together, this chorus of voices tells of the plight of the urban Native American — grappling with a complex and painful history, with an inheritance of beauty and spirituality, and with communion and sacrifice and heroism.

Hailed as an instant classic, “There There” is at once poignant and unflinching, utterly contemporary and truly unforgettable.

Recommended by Keith Weimer, Librarian for History and Religious Studies

“Path Lit By Lightning” by David Maraniss (Simon & Schuster, 2022) and “Mixed Bloods and Tribal Dissolution” by William Unrau (University Press of Kansas, 1989)

“Path Lit By Lightning” by David Maraniss (Simon & Schuster, 2022) and “Mixed Bloods and Tribal Dissolution” by William Unrau (University Press of Kansas, 1989)

For this year’s Native American Heritage month readings, I chose books about two of the most “successful” Native Americans of the 20th century — “Path Lit By Lightning,” David Maraniss’ 2022 biography of Jim Thorpe (a member of the Sac and Fox tribe), often hailed as the greatest athlete of all time; and “Mixed Bloods and Tribal Dissolution: Charles Curtis and the Quest for Indian Identity,” William Unrau’s 1989 biography of Herbert Hoover’s vice president, who was a member of the Kaw Nation. (Despite its cringeworthy title, Unrau’s book remains the only biography of Curtis available.)

Although both men were biracial, Curtis was much more grounded in the world of his white relatives and had a base of capital in the tribal land inherited from his mother’s family, which he used to launch and sustain his political career. He was a strong proponent of assimilation, sponsoring the Curtis Act of 1898, which abolished the authority of tribal courts and tribal law, and strengthened the privatization of tribal land, much of which became prey for white land developers.

Thorpe, a descendant of the iconic warrior Black Hawk, who had led some of the last resistance to white settlement east of the Mississippi, grew up among the Sac and Fox tribe in Oklahoma and attended boarding schools based on a concept of forced assimilation into white culture — most famously Carlisle Academy, where he excelled at football, baseball, and track and field. He won gold at the 1912 Olympics, then had his medals taken away after revelations that he had played two summers of minor league baseball (a humiliation during which he received no support from either Carlisle or his mentor, Coach “Pop” Warner). His remaining life seemed like a decline from early promise, although it still included some remarkable triumphs, as well as activism on behalf of Native Americans. While some of Thorpe’s difficulties stemmed from his personality, they also resulted from a lack of the kind of starting capital and firm connections possessed by Curtis.

Recommended by Cecelia Parks, Undergraduate Student Success Librarian

“Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands” by Juliana Barr (University of North Carolina Press, 2007)

“Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands” by Juliana Barr (University of North Carolina Press, 2007)

Publisher’s summary: Revising the standard narrative of European-Native American relations in America, Juliana Barr reconstructs a world in which Native Americans were the dominant power and Europeans were the ones forced to accommodate, resist, and persevere. She demonstrates that between the 1690s and 1780s, Indigenous peoples, including Caddos, Apaches, Payayas, Karankawas, Wichitas, and Comanches, formed relationships with Spaniards in Texas that refuted European claims of imperial control.

Barr argues that Native Americans not only retained control over their territories but also imposed control over Spaniards. Instead of being defined in racial terms, as was often the case with European constructions of power, diplomatic relations between Native Americans and Spaniards in the region were dictated by Native American expressions of power, grounded in gendered terms of kinship. By examining six realms of encounter — first contact, settlement and intermarriage, mission life, warfare, diplomacy, and captivity — Barr shows that Native American categories of gender provided the political structure of Native American-Spanish relations by defining people’s identity, status, and obligations vis-à-vis others. Because Native systems of kin-based social and political order predominated, argues Barr, Native American concepts of gender cut across European perceptions of racial difference.

Recommended by Haley Gillilan, Undergraduate Student Success Librarian

“Reservation Dogs” on FX Hulu

“Reservation Dogs” on FX Hulu

“Reservation Dogs” is a slice-of-life comedy about four Native American teenagers living on a reservation in Oklahoma. In its short, two-season run, it’s broken barriers for Indigenous filmmaking and representation, with an almost entirely Indigenous cast and crew. While at first it seems that the show is simply about four teens hanging out and having normal high school problems, the plot slowly reveals deep interpersonal and internal conflicts. Bear, Elora, Willie Jack, and Cheese are trying to make their way to California, but will their different values and ways of dealing with grief tear them apart before they get there? “Reservation Dogs” is filled with slow, spiritual, and meaningful moments while also doling out huge laughs and brilliant comedic performances. It’s been renewed for a Season Three, so I highly recommend catching up on the first two seasons and diving into this beautiful TV show!

“Firekeeper’s Daughter” by Angeline Boulley (Henry Holt, 2021)

“Firekeeper’s Daughter” by Angeline Boulley (Henry Holt, 2021)

Angeline Boulley has described the main character of her book as an Indigenous Nancy Drew, and the comparison feels apt! Eighteen-year-old Daunis Fontaine is trying to find her way in her Ojibwe community, but for several reasons is struggling to fit in. When tragedy strikes, she is thrust into a police investigation dealing with some corruption in her town. But as she gets deeper into the mystery, it gets harder and harder to know whom to trust. The stakes for Daunis and her family are high, and she’s going to have to rely on her instincts more than ever. This YA novel is perfect for those seeking a thriller with a true crime vibe, featuring a smart protagonist and a community that’s often underrepresented. Some of subject matter can be heavy and hard to read, but Boulley handles these moments with care and nuance.

Is your favorite piece of Native American literature or media missing from this list? Find us on Twitter @UVALibrary and let us know!

Does the UVA Library not have something you think we should have? Submit a purchase recommendation!

Want to make your work open access? The Library can help.

In his 1973 book, “The Sociology of Science,” the influential American sociologist Robert K. Merton declared: “All scientists should have common ownership of scientific goods (intellectual property) to promote collective collaboration.” This “Mertonian norm,” as it came to be known, long predated the internet (Merton first theorized it in 1942), but some scholars see it as a founding principle of the open access movement, which argues that knowledge should be free, online, and legal to reuse and share.

Merton died in 2003, but aspects of his ideas about collective scientific collaboration live on in policy recently announced by the federal government. In late August, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released new guidance to make the results of federally funded research immediately available to the American public at no cost. The policy memo was a boon to many U.S. academics, researchers, and librarians, who for years have been advocating with a wider international community for open access and open scholarship. The White House directed all federal departments and agencies to implement the new policy by the end of 2025, meaning that paywalls and embargos on taxpayer-supported research will soon be a thing of the past.

Merton died in 2003, but aspects of his ideas about collective scientific collaboration live on in policy recently announced by the federal government. In late August, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released new guidance to make the results of federally funded research immediately available to the American public at no cost. The policy memo was a boon to many U.S. academics, researchers, and librarians, who for years have been advocating with a wider international community for open access and open scholarship. The White House directed all federal departments and agencies to implement the new policy by the end of 2025, meaning that paywalls and embargos on taxpayer-supported research will soon be a thing of the past.

The University of Virginia Library has long supported the open access movement and provides multiple services to assist faculty, scholars, and researchers with making their work open and freely available to the public. In honor of International Open Access Week, we spoke with Brandon Butler, the Library’s Director of Information Policy, about the new policy and what it means for the University. Butler, a copyright lawyer, serves on a UVA-wide open scholarship working group, which will be holding an Open Scholarship Town Hall for UVA faculty on Oct. 24. “I’m a big advocate for open access,” Butler said. “I want to help anybody in the University community who has questions or concerns or is interested in sharing their research in a new way.”

An edited version of our conversation is below:

Q. When would you say the open access movement started? Was it during the dawn of the internet, or does it go back before that?

A. Open access was essentially a movement that was created in scholarship as a reaction to the feeling that it doesn’t make sense to put scholarly work behind a paywall when the internet makes it simple to make things free. The timeline for the movement, can go pretty far back, all the way to the wonderful sociologist Robert Merton, who argued that the ethic of scholarship and research is that what you make should be shared with the world. If you’re making things and withholding them and hoping to charge fees, then that’s not entirely consistent with the values of science. So, the values go way back.

But open access, as we know it today, is strongly connected with the internet. If you wanted to find the perfect inception point, you might look to the Budapest Open Access Initiative. This was a declaration authored in early 2002 by some of the leading thinkers about the ethics and economics of science. They wrote: “An old tradition and a new technology have converged to make possible an unprecedented public good. The old tradition is the willingness of scientists and scholars to publish the fruits of their research in scholarly journals without payment, for the sake of inquiry and knowledge. The new technology is the internet. The public good they make possible is the world-wide electronic distribution of the peer-reviewed journal literature and completely free and unrestricted access to it by all scientists, scholars, teachers, students, and other curious minds.” Ever since then, we’ve been trying to figure out how to change the way we do scholarship to meet that simple opportunity.

Q. How has the UVA Library worked to support this movement? And what are some of the main resources it offers in terms of open access?

A. I would say it’s a four-part answer.

- We support repositories, which are robust, preservation-quality places where scholars who want to make their work open can put their work, and it will be accessible and findable by any scholar in the world because our systems are library-quality. The work will be preservable forever. These repositories are free for any UVA-affiliated author to deposit their work into. They include Libra for articles and other scholarly output, and we also have Libra Data, which is for datasets. The repositories are primarily self-serviced; you make your own deposits, but we’ve got the tools there for you and we’ve got people who can answer your questions.

- The second open access pillar here is our Library publishing operation, which is called Aperio. It’s a press, and it lives in the Library. The goal of Aperio is to help make it easy for faculty and students at UVA who want to create a new open access journal, or who want to publish a new open access scholarly book. We have four journals now that are using Aperio. And it’s free, both to the reader and the author. Some of the open access publishing models out there require authors to pay a fee to cover the cost. Generally, these fees are way too high and they create a real barrier for authors. Our goal all along has been to eliminate that fee — recently, we were able to do that. Every Aperio journal and book is peer-reviewed; these are publications that are up to the same standards of quality as any other scholarly journal or book in the fields where they operate.

- The third pillar here is our Research Data Services + Sciences team. The original Budapest Open Access declaration talked only about journal articles, but over the last 15 years we’ve seen an evolution to recognizing that some of the most valuable scholarly products are data sets — the raw data, that’s the real stuff. So, our Research Data Services team does a lot of powerful work in support of open access. They help people get their data into good shape and develop the kind of data management plans that funders are asking for. That way the data that ends up in an open repository or published somewhere freely available for reuse is in a form that people can actually use.

- I’m saving the least for last, but that’s me. There are, of course, legal questions and policy questions that come up. I can help individual authors figure out what their contracts really If they choose to publish with a particular journal publisher, how can they make their work more open? I also help folks who are embarking on a research project and want the results to be open, but they don’t know how to do that. They may wonder, “How do I put a license on data? What license should I use?” I can’t be everybody’s lawyer, but I can educate them, and help them understand what the choices are and what they mean.

Q. What are your thoughts on the new White House policy?

A. The new White House policy is fantastic. It is a dream come true. It is the kind of change that open access activists have been trying to achieve for literally two decades, since the beginning of the movement. We’ve been going to funders, including the federal government, and saying, “Don’t you think that when you pay for research, the results should be available to everyone?” That’s been the fundamental case we’ve been making all along. COVID and then monkeypox changed things. In the COVID pandemic, publishers made a lot of research freely available temporarily. And then when the monkeypox outbreak came around, federal health agencies asked publishers to make monkeypox-related research freely available, but many publishers balked. I think it just really drove home to the federal research funders that this is absurd — we should not be begging for our own research. That’s where this memo comes from. It pushes the idea that an embargo is just not a tolerable compromise anymore; everything needs to be free and immediately available in order to really accelerate science.

They also expanded the policy to every federal agency that funds research. So that means National Endowment for the Humanities, National Endowment for the Arts, federal social science funding — all that is going to be covered by this policy. And it’s not just about the articles, it’s about the data; the data that is behind every published article that comes from federal funding will also have to be free and open. And that’s huge.

The other thing that’s meaningful about this memo is that it is really beginning to harmonize with the broader conversation in the global open access community that it’s not just about articles; it’s about data. It’s also about things that are a little less sexy, like persistent identifiers [a long-lasting reference to a document, file, web page, or other object]. This is real librarian stuff — metadata.

Everyone around the world is now moving in this direction. Even private funders, like the Gates Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, all these people are now starting to sing from the same hymnal. And that’s really important.

Q. What can you tell me about the UVA open scholarship working group?

A. It’s a great group, and it predates the memo. It originated with the National Academies of Science, and supported by open research funders like the Gates Foundation, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Heart Association, and the American Cancer Society. Upwards of 50 universities are working with this larger group to help scholars create a smoother path toward open practice. The UVA group is working to identify University policies that will help promote open scholarship here on Grounds.

Our open meeting on October 24 is an event for faculty, especially faculty members who are ambivalent about open scholarship work. This first meeting is meant to explain the global trend in favor of open scholarship, what the Library does to support it, and what our working group is thinking about the federal policy. The ultimate goal is to hear the faculty out, to allow them to ask all the questions so we can make sure that whatever we do is responsive to the concerns and interests that the faculty raise. The provost’s office will present, along with Phil Bourne, dean of the School of Data Science; Brian Nosek from the Center for Open Science; Dean of Libraries John Unsworth; and me.

Q. Anything else you’d like to add?

A. I’ve hinted all around this, but the thing that I think has to be said as explicitly as possible is that the No. 1 barrier to open practice is outdated promotion and tenure standards. And until the scholarly disciplines can evaluate research in a way that is not reliant on journal brands and journal metrics, we’re not going to make progress on this problem. It’s a big barrier that we’re going to have to get through, so I feel like it’s important to bring that up. Our goal at the Library is to help academic departments understand the value of open practice and help them see that it would be good to reward that practice.

Recommended reading for Hispanic Heritage Month

Thanks to Amy Hunsaker, Librarian for Music & the Performing Arts, for contributing this post.

From magical realism master Gabriel García Márquez to exciting debut novelist Xochitl Gonzalez, there are thousands of Latinx authors to celebrate during Hispanic Heritage Month, which overlaps September and the first few weeks of October.

We’ve gathered some book recommendations from UVA librarians and Ph.D. candidates from the Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese Department.

Take a look at their selections below. (For a more extensive list, see this guide.)

Recommended by Katie Rojas, Head of Archival Processing

“The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina” by Zoraida Córdova (Atria Books, 2021)

One of my favorite literary styles is magical realism, and this book did not disappoint. Córdova’s novel tells the story of the Montoya family and the strange blessings of their matriarch, Orquídea Divina. Even her name, which means “Divine Orchid” alludes to the delicate and mysterious beauty of orchids, which must have just the right conditions to bloom and thrive. Orquídea Divina lives up to her name, never leaving her home, yet creating a flourishing landscape and bounty of food in a place that was once barren. Upon receiving invitations to Orquídea Divina’s funeral, three of her adult grandchildren travel back to their family’s small hometown of Four Rivers and embark upon a journey of discovery, self-preservation, and family history which leads them to Ecuador. As an archivist, I especially love how the themes of family origin, identity, and place all relate well to current understandings of how the history of our families impacts us today. I recommend this book to anyone who enjoys fantasy, light horror, and stories of self-discovery.

(UVA Library hardcover copy is on order.)

Recommended by Amy Hunsaker, Librarian for Music & Performing Arts

“Mexican Gothic” by Silvia Moreno-Garcia (Del Rey Books, 2020)

This spooky book set in remote Mexico in the 1950s brings the reader into a gothic horror setting that includes an eerie house, ghoulish relatives, a haunted, forbidding cemetery, and Noemí, the stylish and clever socialite who must solve the mysteries surrounding High Place manor. Is there a perfectly scientific explanation for the supernatural aberrations that seem to be spiraling our hero toward certain doom? Will she be able to save herself and her cousin from a fate worse than death? Is there anyone she can trust? Will you, gentle reader, be able to look at mushrooms in the same way ever again?

(UVA Library hardcopy is on order.)

“Love in the Time of Cholera” by Gabriel García Márquez, translated from the Spanish by Edith Grossman (Knopf, 1988)

Florentino Ariza lives only for love. He only wants to die for love. But his most sincere love isn’t requited.

“… his examination revealed that he had no fever, no pain anywhere, and that his only concrete feeling was an urgent desire to die. All that was needed was shrewd questioning … to conclude once again that the symptoms of love were the same as those of cholera.”

The obsessed Ariza can never be cured of his lovesickness for Fermina Daza in a story that spans several decades, explores the complexities of relationships, and illustrates how noble it is to suffer for love. Márquez’s luscious storytelling poetically explores themes of love, philosophy, and life in general.

(Available in Spanish; Electronic Copy: Internet Archive)

Recommended by Miguel Valladares-Llata, Librarian for Romance Languages and Latin American Studies

“Olga Dies Dreaming” by Xochitl Gonzalez (Flatiron Books, 2022)

Publisher’s summary: “A blazing talent debuts with the tale of a status-driven wedding planner grappling with her social ambitions, absent mother, and Puerto Rican roots, all in the wake of Hurricane María.”

“Neruda on the Park: A Novel” by Cleyvis Natera (Ballantine Books, 2022)

Publisher’s summary: “An exhilarating debut novel about members of a Dominican family in New York City who take radically different paths when faced with encroaching gentrification, for readers of ‘Such a Fun Age’ and ‘Dominicana.’”

“Brown Neon: Essays” by Raquel Gutiérrez (Coffee House Press, 2022)

Publisher’s summary: “Part butch memoir, part ekphrastic travel diary, part queer family tree, Raquel Gutiérrez’s debut essay collection ‘Brown Neon’ gleans insight from the sediment of land and relationships. For Gutierrez, terrain is essential to understanding that no story, no matter how personal, is separate from the space where it unfolds.”

(On order for Clemons Library.)

Recommended by Carlos Velazco Fernandez, Ph.D. Candidate

“La mucama de Omicunlé” de Rita Indiana (Editorial Periférica, 2015)

Publisher’s summary: “This overwhelming novel, which enshrines Rita Indiana as narrator, contains many layers and fascinating twists. … Including deities that inhabit the Caribbean Sea, political interests, Goya’s prints, gender reassignment and numerous plot twists, few other works of fiction speak of contemporary art as precisely as ‘La mucama de Omicunlé.’”

“Tentacle” by Rita Indiana, translated by Achy Obejas (And Other Stories, 2018)

Publisher’s summary: “Plucked from her life on the streets of post-apocalyptic Santo Domingo, young maid Acilde Figueroa finds herself at the heart of a voodoo prophecy: only she can travel back in time and save the ocean and humanity from disaster. … Bursting with punk energy and lyricism, it’s a restless, addictive trip: ‘The Tempest’ meets the telenovela.”

The other two books are poetic since poetry is the water of the soul. Besides, these books are close to our university, since the first one was written by a guest professor at our university last year and the second one is written by another professor who currently teaches at our university:

“Adiós a Lenin: Antología Poética” de Federico Díaz-Granados (Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2017)

Publisher’s summary: “Ultimately, only the poetic word is capable of evoking the lost paradise of childhood, family, love, the desired body, the longed-for plenitude. Yes, to evoke them, but only in fragments and scraps, in their traces and absences, in their ‘brief passage through the word.’ Hence precisely the tragic beauty of the poetry of Federico Díaz Granados.”

“America” by Fernando Valverde, translated and with an introduction by Carolyn Forché (Copper Canyon Press, 2021)

Publisher’s summary: “In Fernando Valverde’s América, ‘sorrow is ancient.’ Mournfully lyrical, politically sharp, with a sweeping view of American roots, dysfunctions, and ideals – as if from above, and yet also from within – this is a book that deconstructs the legacy of empire. Valverde is widely regarded as one of the most important younger Spanish-language poets. Here his vibrant voice and convictions are translated and introduced by Carolyn Forché, herself a world-renowned poet of witness. Bilingual, with Spanish originals and English translations.

Recommended by Elizabeth Mirabal, Ph.D. Candidate

“El infinito en un junco: la invención de loss libros en el mundo antiguo” de Irene Vallejo. (Siruela, 2019)

Publisher’s summary: “In an essay sprinkled with personal anecdotes, Irene Vallejo breaks down and covers 30 centuries of the history of the book.”

(An English translation will be available in late September.)

“Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World” by Irene Vallejo, translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Whittle (Knopf, 2022)

Publisher’s summary: “A rich exploration of the importance of books and libraries in the ancient world that highlights how humanity’s obsession with the printed word has echoed throughout the ages.”

“Jardín” de Dulce María Loynaz (Aguilar, 1951)

You can electronically read this novel in the critical edition by Zaida Capote Cruz published in 2015 in La Habana, Cuba (Editorial Letras Cubanas), via the Internet Archive. No English translation available.

“My Tender Matador” by Pedro Lemebel, translated by Katherine Silver (Grove Press, 2003)

Publisher’s summary: “Centered around the 1986 attempt on the life of Augusto Pinochet, an event that changed Chile forever, My Tender Matador is one of the most explosive, controversial, and popular novels to have been published in that country in decades.”

New UVA Library exhibition showcases powerful, century-old portraits of Black Virginians

“Visions of Progress: Portraits of Dignity, Style, and Racial Uplift,” a new exhibition at the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, showcases portraits that African Americans in central Virginia commissioned from the Holsinger Studio during the first decades of the 20th century. The photographs expressed the individuality of the women and men who commissioned them, while silently yet powerfully asserting their claims to rights and equality. Opening Sept. 22, the exhibition is the result of years of research by UVA professors, students, and community members.

John Edwin Mason, a UVA associate professor of history and a documentary photographer, first learned about the Holsinger Studio Collection, held in the Small Special Collections Library, when he saw a small exhibition at the UVA’s Woodson Institute, curated by the late professor Reginald Butler and professor Scot French (now of the University of Central Florida) in 1998. The collection, which UVA acquired in 1978, includes about 10,000 glass plate negatives taken by the Holsinger Studio of life in Charlottesville and Albemarle and Nelson counties from the 1890s to the 1920s. Many of the photographs were commissioned portraits and more than 600 of those portraits are of African American citizens in central Virginia. Mason was immediately intrigued.

“I thought that we could use these portraits not simply to enjoy for their beauty as aesthetic objects, but we could see history through them, we could tell history through them. By researching the lives of the people in the photographs, we can learn a lot about the history of this place,” he said.

The portraits were taken during the height of the Jim Crow era, when state laws enforced racial segregation in the South, the Ku Klux Klan had local chapters in the Albemarle region, and a wealthy, white UVA alumnus successfully commissioned two statues of Confederate leaders (Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson) to be erected in Charlottesville parks. “It was an incredibly oppressive time,” Mason said. “But the magic of these portraits is that you don’t see the oppression in them. And that was intentional on the part of the people who had their images made. They are saying, ‘We are not who you think we are. We are not those stereotypes, we are not defined by our status in Jim Crow society.”

A community effort

In 2015, Mason turned his interest in the photos into action. He launched the Holsinger Studio Portrait Project, to delve into the lives of the portrait subjects; a partnership with the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities director Worthy Martin in 2018 provided the project with a web presence to share their research. With a 3Cavaliers grant from the office of UVA’s Vice President for Research, the team was able to hire seven undergraduate students to examine census records, military records, birth and death certificates, and African American newspapers from surrounding regions. They also dug through personal papers in UVA Special Collections to find original Holsinger prints, giving the students information about the people in the portraits and about central Virginia during that era.

A grant from Virginia Humanities allowed the team to begin reaching out to the local community to help identify portrait subjects. In 2019, the project partnered with the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center to host a “Family Photo Day,” where participants could examine the Holsinger Studio portraits in flipbooks and add comments if they had any information about the subjects. “We had over 300 people come to our Family Photo Day,” Mason said. “That was a moment where we could see the potential for the project; we could see how engaged and how excited people were by these portraits.”

That same year, the team also installed 30 of the portraits around the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers construction site, drawing attention from hundreds of passers-by each day. Two Charlottesville community members, Descendants of Enslaved Communities at UVA co-chair DeTeasa Brown Gathers (who found a photo of her great-great grandmother in the Holsinger Studio Collection) and local realtor Edwina St. Rose, joined the project as community advisors. Working with the group The Preservers of the Daughters of Zion Cemetery, they launched an exhibit of the portraits at CitySpace in downtown Charlottesville in the summer of 2019.

A significant grant from the Jefferson Trust earlier this year, awarded to the University’s Corcoran Department of History, IATH, and the UVA Library, is supporting the team to think more broadly about a community engagement program. In March, the team launched a pop-up exhibit of the Holsinger photos at the Northside branch of the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library. “Our trustees were fascinated to learn that such an interesting collection of African American history is held by the University,” said Amy Bonner, director of grants at the Jefferson Trust. “The opportunity to help launch such a powerful exhibition and support the associated research was impossible to pass up.”

Viola Green Porter (1898-1985) commissioned this portrait to commemorate her graduation from the eighth grade at Charlottesville’s segregated Jefferson Graded School. The white dress and diploma make this photo similar to other Holsinger Studio graduation portraits of young women, both Black and white.

The grant is also supporting the “Visions of Progress” exhibition launching Sept. 22 in the Main Gallery of the Small Special Collections Library, where visitors can view almost 100 Holsinger Studio portraits and take in the biographical information about the subjects unearthed over the past few years by the Holsinger Studio Portrait Project team. They can also learn about the “New Negro” movement that countered the Jim Crow oppression of the early 20th century, stemming from Black intellectual leaders Booker T. Washington, Alain LeRoy Locke, and Charlottesville native George W. Buckner, whose manifesto, “The New Negro,” caused an uproar when the Charlottesville Messenger, the city’s Black newspaper, published it in 1921. “The New Negro the country over is coming to see that his salvation is in his own hands,” Buckner wrote.

The portraits in the exhibit reflect this ethos, Mason said. “It’s important to emphasize that even though the people in the portraits are dressed to the nines, they are everyday people. Most had working-class jobs.” By dressing so beautifully, Mason said, the portrait sitters were pushing back against racist caricatures that were common in American media during that era. “There was dynamism within the African American community,” he said. “Immediately after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, over 100 African American women registered to vote in Charlottesville. Black people were running barber shops, running blacksmith shops, running laundries, and campaigning for a high school. People were not defined by their oppression.”

Vibrant portraits

In 2020, Holly Robertson, Curator of University Library Exhibitions, reached out to Mason to suggest co-sponsoring an exhibition after seeing the enthusiasm the Holsinger Portrait Project garnered on Grounds in the community.

“The Holsinger Studio portraits have been an important part of the UVA Library’s collections since the 1970s,” Robertson said. “We’ve done so much work to describe and provide access to the collection — it was one of the first photographic collections we fully digitized in the late 1990s, and each portrait is available online through Virgo. We’ve taken painstaking care to provide the best preservation environment for the fragile glass plate negatives as well as the business ledgers. Yet, we’ve never exhibited this collection. As the Holsinger Studio Portrait Project grew, we saw a wonderful opportunity to partner in telling the stories of Black central Virginians through our amazing collections.”

UVA Library staff played a crucial role in preparing the portraits for the Special Collections exhibition. Stacey Evans, an imaging specialist and project coordinator for the Library, led a team in rephotographing the glass-plate negatives to capture plate identification numbers that had been cropped in scanning efforts in the 1990s. This helped to identify photo subjects. By following standards set by the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative, Cultural Heritage Imagining, and the Library of Congress, Evans and her team then took their photographic reproductions of the negatives and created “artist’s renderings” of the portraits using Photoshop.

Evans, a photographer who has nearly 30 years of experience scanning negatives and working in digital imaging, said that when comparing the original scans of the negatives in Virgo to the images her team created, the tonal range of the portraits has dramatically improved. “On a personal note,” she said, “John Mason and I have been friends in the Charlottesville photo community for many years. It’s an honor to work with him on this project.”

Brandon Butler, the Library’s Director of Information Policy, conducted extensive research on copyright issues pertaining to the Holsinger collection to prepare for the exhibition. “Perhaps surprisingly, some portraits in the Holsinger Studio Collection are still subject to copyright regulations more than 100 years after they were created,” Butler said. “We believe the portrait copyrights belonged to whoever paid to have them taken — often the subject or a relative. Because that right would endure for 120 years, the descendants of the portrait sitters may still hold rights to their ancestors’ images.”

Mason and Library staff members urge exhibition visitors who might recognize ancestors or have any information about the portrait subjects to email the team at

HolsingerStudio@virginia.edu. A brochure of the portraits will be freely available at the opening, and the Holsinger Project website, built by IATH, will live on after the exhibition ends in June 2023. With further support from the Jefferson Trust grant, the Holsinger Studio Project will continue to bring the portraits into the local community, visiting schools, religious organizations, and civic groups. An exhibition at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center curated by Andrea Douglas, the center’s Executive Director, is in development.

“We want to change the way that everyone in central Virginia sees our shared history,” Mason said.

Public exhibition opening details

The public opening celebration for “Visions of Progress: Portraits of Dignity, Style, and Racial Uplift” will be held on Sept. 22 in the Main Gallery of UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library from 5-8 p.m.

John Edwin Mason will host two rounds of gallery talks that evening: one at 5:30 p.m., another at 6:30 p.m.

Kendall King and Jalane Schmidt, curators of another UVA Library exhibition, “No Unity Without Justice: Student and Community Organizing During the 2017 Summer of Hate,” will speak in the First Floor Gallery at 6 and 7 p.m.

This event is free, but registration is required: 100 tickets will be released via EventBrite for the 5:30/6:00 talks, and another 100 for the 6:30/7:00 talks. Register here: https://Visions-UVA.eventbrite.com

A shuttle will run from the Jefferson School African American Center to the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at UVA every 30 minutes from 4-8 p.m. for the public opening celebration on September 22, 2022. Registered attendees may also request a code to park for free in the Central Grounds Garage.

For reporters

For press inquiries, please contact Elyse Girard at elyse@virginia.edu.

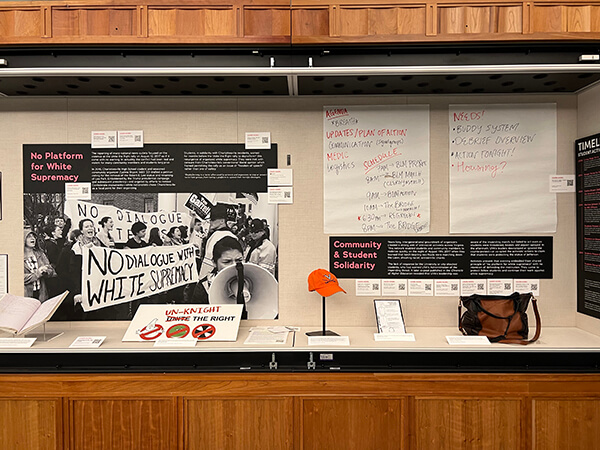

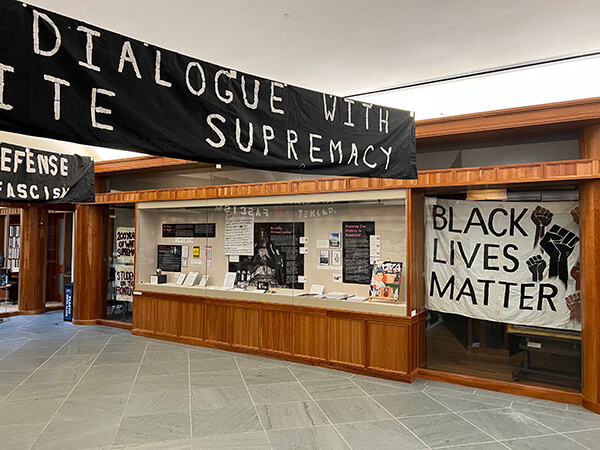

New UVA Library collection, exhibition examine ‘Summer of Hate’ through first-person lens

Five years ago this week, community organizers, activists, students, and residents of Charlottesville stood up to an unprecedented wave of far-right hate and terror. Several hundred white supremacists marched at the University of Virginia and in downtown Charlottesville as part of the “Unite the Right” rally, events that led to violence and three deaths. Immediately following the weekend of Aug. 11 and 12, 2017, senior leaders at the University of Virginia Library asked curators and archivists to collect both physical and digital materials related to the rally.

Library staff got to work, gathering accelerants and tiki torches that had been thrown in bushes; white supremacist propaganda left in driveways; and posters and banners from students, faculty, staff, and community members who had counter-protested the white nationalists. UVA curators teamed up with the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library to collect images, videos, and stories about the rally from the local community. At the same time, digital preservationists were gathering rally-related tweets, photos, and postings online before they disappeared, including hateful speech from places like 4chan. It was challenging work.

“We realized that we hadn’t prepared for this. Although we had been working towards developing workflows for collecting born-digital content, we didn’t have the infrastructure in place to support the technological challenges or emotional challenges of the work,” said Kara M. McClurken, the Library’s Director of Preservation Services. “From my own perspective, as a manager, I wasn’t sure how to best support my staff who were being asked to do things like stabilize the tiki torches used to threaten and harm our students and a Library colleague.”

This crash course in what McClurken describes as “collecting in times of crisis” led the Library to form a Digital Collecting Emergency Response Group, which sought advice from other institutions that had experienced tragedies in their communities. “After the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida, a group of archivists found themselves feeling similarly,” she said, and they asked the Society of American Archivists to explore ways to provide support for communities documenting in times of crisis. The Library also applied for and received a grant from the nonprofit LYRASIS, which they used to develop resources and toolkits to help institutions be better prepared to implement digital collecting strategies during and after crises.

Now, UVA Library has an official Digital Collecting Emergency Response team, led by McClurken, who also serves as co-chair of the Society of American Archivists’ Crisis, Disaster, and Tragedy Response Working Group. “Within UVA Special Collections, this experience (as well as larger discussions in the archival community) has changed our way of viewing our work — we have a group of folks who now meet regularly to discuss a trauma-informed approach to our spaces and collections, and to consider the impact of harmful or difficult content,” she said.

Many of the digital items UVA Library staff collected in the days after rally are now available to the public in the “University of Virginia Collection on Events in Charlottesville, VA, August 11-13, 2017,” a 20 gigabyte digital archive, containing everything from a video of white supremacists marching up the Rotunda steps the night of Aug. 11, to a recollection of a helicopter that hovered over the city for hours on Aug. 12, to a compilation of statements by institutional leaders at Virginia colleges and universities condemning hateful ideologies.

McClurken emphasized that it was a multi-departmental Library team that gathered the materials from many different sources, noting specifically the efforts of Joseph Azizi, the Library Stacks Coordinator in Special Collections; Stacey Lavender, the Project Digital Archivist; and Lauren Work, the Digital Preservation Librarian. “I was amazed at all the ‘firsts’ they accomplished to get this collection ready,” she said. “This type of collecting in times of crisis often requires many hands.”

New exhibition centers on alumni and community activist experience

Today, the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library is launching a new exhibition, “No Unity Without Justice: Student and Community Organizing During the 2017 Summer of Hate,” which will be on display in the First Floor Gallery through October 29, 2022. The exhibition is distinctive in that it was largely curated by UVA alumni who took part in the anti-fascist counter-protests in the summer of 2017 when they were students.

“In recent years, we’ve sought curatorial partnerships with the people and places on whom we place the lens of focus,” said Curator of University Library Exhibitions Holly Robertson. “Every curator brings a perspective — and necessarily their experience — to every exhibition. ‘No Unity Without Justice’ may be unique in that the curators have offered us a first-person perspective based on being fully embedded on the frontlines of Charlottesville just five short years ago.”

The 37-item exhibition provides personal narratives of the curators’ experiences, as well as those of various Charlottesville community activists. It was primarily curated by Kendall King, a 2018 UVA alum, artist, and community organizer; in partnership with Jalane Schmidt, a UVA associate professor of religious studies; with guest alumni curators Natalie Romero, Hannah Russell-Hunter, and Memory Project postdoctoral fellow Gillet Rosenblith. King and Romero pitched the exhibition idea to Special Collections when they were still students.

The exhibit is in partnership with the UVA Democracy Initiative’s Memory Project, and the study of democracy is a priority research area in the University’s 2030 Strategic Plan. Schmidt, who directs The Memory Project, said the exhibition aligns with the Project’s mission to sponsor events that promote more inclusive, democratic narratives of history. She worked with the curators to ensure the exhibition’s historical accuracy; all sources are cited in the exhibition and many objects include QR codes linking to news articles, Charlottesville City Council meeting minutes, and a successful civil lawsuit against organizers, promoters, and participants of the Unite the Right rally. “I have been impressed by the students’ energy in documenting these events,” she said. “Memory is not always pretty; it can be painful.”

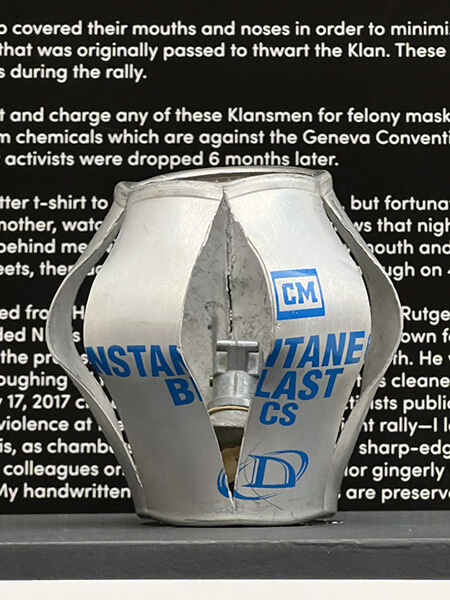

The exhibition includes not only the personal items of the alumni curators and community members (a tear gas canister launched at counter-protestors during a Ku Klux Klan rally in Charlottesville in July 2017; a shoulder bag used by an activist as a makeshift shield to protect students around the Jefferson statue on August 11; a student notebook with poetry, songs, sketches, and research from summer 2017), but also objects and papers related to UVA student activist history, dating back to the 1969 founding of the UVA Black Students for Freedom group.

“I hope visitors will also gain an appreciation for Charlottesville and the University’s deep, rich organizing tradition that has resulted in many victories in the past decades,” said alum curator Russell-Hunter. “It was really gratifying to articulate my experiences as a survivor — including observations and analyses that I have literally been thinking about for years — with the knowledge that it was going to reach a wide audience. I’m grateful to the Special Collections staff for giving us the space to create an honest narrative of the events of the summer of 2017.”

Robertson said she hope the exhibition is “a cathartic thing. That’s how we set up the space — it’s a place to move through another person’s experience and also to reflect on your own, whether you were there on Aug. 11 and 12 or not. We’re deeply grateful to the curators for entrusting us with their archives and their stories.”

Take a look at some of the objects in the “No Unity Without Justice” exhibit below.

“No Unity Without Justice” remains on view until October 29, 2022. See Library hours and parking information.

Press inquiries: Elyse Girard, elyse@virginia.edu.

Celebrating a Milestone of the Main Library Renovation

University and Library personnel and construction workers and contractors gathered yesterday for a "topping-out ceremony" for the library renovation. The topping-out is when the last beam is placed atop a structure, and is a traditional milestone in a major construction project.

The beam was signed by Library staff, UVA facilities personnel, construction workers, and others involved in the project. Chris Rhodes, Skanska senior project manager; John Unsworth, the University librarian and dean of libraries at UVA; and Mark Stanis, director of construction for UVA, delivered remarks thanking the tradespeople involved. The remarks were translated into Spanish for the benefit of all by carpenter Alex Alverez.

The topping-out ceremony symbolically marks the transition in construction away from the exterior of the building and into a new phase as the structure is "closed up" and the interior work begins. The renovation/construction project, slated to be finished in the fall of 2023, will completely refurbish the historic envelope of the building and add new collections, research, and study space.

Read more and view photos of the topping-out ceremony from UVA Today.

Recommended reading for Jewish American Heritage Month 2022

Recommended by Sherri Brown, Research Librarian for English and Digital Humanities

“Antiquities” by Cynthia Ozick (Knopf, 2021)

“Antiquities” by Cynthia Ozick (Knopf, 2021)

Cynthia Ozick provides the reader with much to ponder in this compact novel. Readers get a glimpse into the thoughts of Lloyd Wilkinson Petrie through the guise of his attempt at writing a memoir. In some ways, Petrie’s attitude and escapades as he attempts to record a moment from his childhood at the Temple Academy for Boys in New York calls to mind a character befitting Donald Petrie’s 1993 film “Grumpy Old Men” or John Madden’s “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” (2011). However, Lloyd Petrie is not a loveable character but an anti-Semite who fluctuates between his own self-aggrandizement and self-doubt. The novel questions the authenticity of memory, the significance of memoir, and the adoration of objects, all while Petrie reflects on a secret infatuation with an outcast among outcasts. One reading only scratches the surface of the treasure embedded in these pages.

“Black, White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self” by Rebecca Walker (Riverhead Books, 2001)

“Black, White and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self” by Rebecca Walker (Riverhead Books, 2001)

Rebecca Walker is the daughter of famed novelist Alice Walker and civil rights lawyer Melvyn R. Leventhal. Her memoir captures the searingly harsh adolescent experience of growing up in the U.S., her childhood made particularly challenging by her multiracial heritage. Walker shares her struggle with finding her identity while feeling ever the outsider. A book that highlights both pain and resilience, this account delves into feelings of not being Black enough, not being white enough, and not being Jewish enough. While this was written more than twenty years ago, it still reflects the state of a nation that is uncomfortable with race and religion and the children who must learn to live with that discord.

“The History of Love” by Nicole Krauss (WW Norton, 2005)

“The History of Love” by Nicole Krauss (WW Norton, 2005)

I first read this book more than ten years ago and gave it three stars out of five on Goodreads. But I picked it up again this past winter, and wow, it really spoke to me this time around! This novel is written in several narrative voices. The chapters narrated by Jewish Polish American immigrant Leo Gursky alone make the book a must read. Leo is nearing the end of his life (or so he believes), and the way he sees the world and relates to it is alternately shocking, funny, sad, and touching. His loneliness is palpable — “All I want is not to die on a day when I went unseen.” This is a book to be read slowly and contemplated to be truly enjoyed. I’m glad I came back to it.

Recommended by Ashley Hosbach, Education and Social Science Research Librarian

“Burning Girls and Other Stories” by Veronica Schanoes (Tordotcom, 2021)

“Burning Girls and Other Stories” by Veronica Schanoes (Tordotcom, 2021)

“When we came to America, we brought anger and socialism and hunger. We also brought our demons.”

“Burning Girls” reclaims the fairy tale genre, viewed here through a Jewish feminist lens that subverts the Grimm brothers’ anti-Semitic tropes. Gripping and dark, Veronica Schanoes’ collection of short stories explores witchcraft, demons, and vengeance, a narrative driven by the fears and hopes of immigrants fleeing their home countries for a better life. However, Schanoes ultimately reveals that the true horrors are not the creatures lurking in the shadows, but instead are the sins of capitalism, the false promise of the “American Dream,” anti-Semitism, and the overwhelming cruelty of humanity.

Recommended by Eyal Handelsman Katz, English Ph.D. candidate at UVA

Handelsman Katz’s dissertation explores parental figures and their ties to feminist and ethnic movements and discourses in 20th and 21st century multiethnic American prose. In collaboration with the UVA Religion, Race & Democracy Lab, he recently produced a short documentary, Słabe Jajko, about his grandmother’s memories of the Holocaust.

“Bread Givers” by Anzia Yezierska (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1925)

“Bread Givers” by Anzia Yezierska (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1925)

When Anzia Yezierska’s family emigrated to the United States from the Polish part of Russia in the 1880s, they Americanized their name, calling themselves the Mayers, with Anzia becoming Hattie Mayer. Yezierska would become a celebrated author in the early 20th century, penning among other novels “Bread Givers” (1925), her most famous work. The novel is a coming-of-age story that follows Sara Smolinsky as she struggles against her caricature of a father and sets out to succeed on her own terms. While the narrative bears the expected tropes of early 20th century feminist writing that often links female independence with whiteness and Americanization, there is more to Yezierska and the novel than meets the eye. How do we reconcile Sara’s attempt to Americanize herself with the author’s resolve to market herself as an ethnic writer under her birth name? Modern readers will also appreciate some of the ways in which the novel predates familiar tropes in rom-coms of the 1990s. Yezierska herself found brief success in Hollywood before becoming ultimately frustrated by its shallowness and alienation.

“The Promised Land” by Mary Antin (Houghton Mifflin, 1912)

“The Promised Land” by Mary Antin (Houghton Mifflin, 1912)

Mary Antin, like Anzia Yezierska, was a Russian Jewish immigrant who moved to the Lower East Side and contributed to a wave of early feminist Jewish writing. “The Promised Land” (1912) was a celebrated and controversial memoir in which she traced her experiences as an immigrant and her embrace of U.S. culture. Antin’s text serves as a key to understanding contemporary issues in Jewish culture: Her vision of Jewish heritage in racial (rather than strictly religious) terms. How do Jews identify themselves, or should they? The question provoked widespread debate in Jewish communities throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which is clear in Antin’s memoir. Crucially, as with Yezierska, Antin offers an intersectional answer: she asks not just what does it mean to be Jewish American, but what does it mean to be a Jewish American woman?

“The Collected Stories” by Grace Paley (Farrar Staus Giroux, 1994)

“The Collected Stories” by Grace Paley (Farrar Staus Giroux, 1994)

Grace Paley’s “The Collected Stories” includes three of her excellent story collections: “The Little Disturbances of Man” (1959), “Enormous Changes at the Last Minute” (1974), and “Later in the Same Day” (1985). In reading these stories, we see the evolution of one of the 20th century’s most talented prose writers. From the youthful energy of her early work (particularly “The Loudest Voice,” wherein a young Jewish girl is given the starring role in her school’s nativity play) to the charmingly adolescent and poignantly existential second collection (including “The Long Distance Runner,” in which a young mother hides herself in her old family home, adopted by its new inhabitants) to her more political later work (such as “Listening,” where she offers a form of activism based on the power of small gestures we can do for each other), one cannot help but be seduced by Paley’s verve, gentleness, and humor.

“The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick (1980). Printed in book format by Knopf, 1989.

“The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick (1980). Printed in book format by Knopf, 1989.

Theodor Adorno famously stated that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” How can one write anything that aims to represent such atrocities? In other words, can or should the Holocaust be represented? Many authors have taken various approaches to writing about the Holocaust, from the purely factual to the comic and beyond. Cynthia Ozick’s famous short story, “The Shawl,” seeks to represent the Shoah not through fact, but through feeling. A deeply visceral story, “The Shawl” follows Rosa, a mother trying against all odds to survive the concentration camps, with Ozick’s magical realism serving as a way to navigate a reality so awful and tragic that it seems as if it could only be unreal (an approach not without detractors). Please check out Ozick’s sequel “Rosa,” which follows some of the characters as they attempt to live on in the aftermath of unshakeable trauma.

“Days of Awe” by Achy Obejas (Ballantine Books, 2001)

When someone told Achy Obejas that her surname suggested that she had Jewish ancestry, she was motivated to dig deep into her family history. Her discoveries led her to write “Days of Awe” (2001), which, while not autobiographical, allowed her to reflect on the history of what are known as “crypto-Jews” (Jews who secretly adhere to Judaism while outwardly professing another faith, especially Sephardic Jews who faced forced conversion in Spain). “Days of Awe” follows Alejandra, a Cuban American woman who, in her travels back to Cuba, uncovers her father’s secret Jewish heritage. Through Alejandra’s plight as a lesbian woman navigating what it means to be a Jewish Cuban immigrant in the United States, Obejas offers us a complex commentary on the very notion of ethnicity.

When someone told Achy Obejas that her surname suggested that she had Jewish ancestry, she was motivated to dig deep into her family history. Her discoveries led her to write “Days of Awe” (2001), which, while not autobiographical, allowed her to reflect on the history of what are known as “crypto-Jews” (Jews who secretly adhere to Judaism while outwardly professing another faith, especially Sephardic Jews who faced forced conversion in Spain). “Days of Awe” follows Alejandra, a Cuban American woman who, in her travels back to Cuba, uncovers her father’s secret Jewish heritage. Through Alejandra’s plight as a lesbian woman navigating what it means to be a Jewish Cuban immigrant in the United States, Obejas offers us a complex commentary on the very notion of ethnicity.

Recommended by Hannah Jane LeDuff, UVA alum

Hannah Jane LeDuff earned her Master’s degree in English with a concentration in World Religion and World Literature in 2021. She is currently an editor for a committee of the Mississippi Legislature.

“The Book of Separation: A Memoir” by Tova Mirvis (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018)

“The Book of Separation: A Memoir” by Tova Mirvis (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018)

Tova Mirvis’s memoir details her own journey of leaving her Orthodox Jewish marriage and community to explore the unmapped terrain of a world outside of the religion and tradition in which she was raised. This memoir inspires readers to live their lives true to themselves without the fetters of the expectations of others.

Also recommended by Hannah Jane:

- “A Letter to Harvey Milk: Short Stories” by Lesléa Newman (University of Wisconsin Press, Terrace Books, 2004)

- “The Ladies Auxiliary” by Tova Mirvis (WW Norton, 1999)

- And for children: “Welcoming Elijah: A Passover Tale with a Tail” by Lesléa Newman (Charlesbridge, 2020)

Researchers can direct queries about Jewish American literature to Sherri Brown and research questions regarding Jewish Studies to Miguel Valladares-Llata, Librarian for Romance Languages and Latin American Studies, whose subject specialties include French, German, Jewish Studies, Latin American Studies, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese.

Celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage with some great reads!

May is Asian American and Pacific American Heritage Month! Celebrate by reading literature, poetry, and more by Asian American and Pacific Island artists. Here’s a list prepared by Undergraduate Student Success Librarian Haley Gillilan to get you started.

POETRY

“Night Sky with Exit Wounds” by Ocean Vuong

“Night Sky with Exit Wounds” by Ocean Vuong

This critically acclaimed and award-winning poetry collection by Vietnamese American author Ocean Vuong is centered around diaspora, queer love, and the author’s relationship with his mother. As a poet, Vuong is careful and thoughtful, and very focused on craft and form.

His novel, “On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous,” is a semi-autobiographical work in which a son writes a letter to his mother. Vuong also recently released a new poetry collection, “Time Is A Mother.“

READ BEFORE YOU WATCH

“Pachinko” by Min Jin Lee

“Pachinko” is a saga that spans decades, following four generations of a Korean family as they navigate migration, exile, and shifting power dynamics. This beautiful story asking timeless questions about home, identity, and culture is perfect for anyone who loves historical dramas. It has recently been adapted into a miniseries for Apple TV+, featuring award winning actress Youn Yuh-Jung and popular K-drama actor Lee Min-Ho.

MEMOIR

“Another Appalachia: Coming Up Indian and Queer in a Mountain Place” by Neema Avashia

“Another Appalachia: Coming Up Indian and Queer in a Mountain Place” by Neema Avashia

This book of personal essays follows the experiences of an Indian woman who grew up queer in West Virginia. Avashia’s work is about a very small and close-knit community that exists in a place that seems unlikely and attempts to reconcile nostalgia with the realities of her upbringing. For those seeking a unique and moving portrait of the Appalachian region, this book is for you.

MYSTERY COMEDY

“Dial A For Aunties” by Jesse Q. Sutanto

I have heard this book described as a “Crazy Rich Asians” meets “Weekend at Bernies,” and I don’t think a description could possibly be more accurate. “Dial A For Aunties” will take you on a rollercoaster that never stops twisting. When Meddy Chan accidentally kills her blind date, her nosy Aunties spring to the rescue. Things get more complicated when the body is accidentally shipped to the billionaire island resort where Meddy and her family are supposed to be working at a wedding that weekend. Can they dispose of the body, pull off the wedding, and dodge Meddy’s college ex-boyfriend all at the same time? Find out in this hilarious, page-turning adventure.

HISTORY

“Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People” by Helen Zia

“Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People” by Helen Zia

For those hoping to learn more about the history of Asian Americans and Asian American activism, this book is a great place to start. The author, Helen Zia, is an important activist and journalist who, when she started speaking out about the murder of Vincent Chin in 1982, energized and coalesced Detroit’s Asian American community. It became a key moment in the larger Asian American movement.

SHORT STORIES

“In the Country” by Mia Alvar

Thanks to Romance Languages and Latin American Studies Librarian Miguel A Valldares- Llata for this contribution.

This first book written by Mia Alvar won multiple awards as soon as it was released in 2016. Its nine short stories evoke not only a past in the Philippines but the personal evolution, nostalgia, struggle, and conflict involved in reaching a new world in New York and Bahrain. It is a book overflowing with family, miracles, girls, legends, and especially Kontrabida (villains, although I prefer the translation as antihero). Written in English and sprinkled with Tagalog (the national language of the Philippines), it shows the desire to conquer a new world from a woman’s vantage point.

GRAPHIC NOVEL

“Boxers & Saints” by Gene Luen Yang

“Boxers & Saints” by Gene Luen Yang

Gene Luen Yang is one of my favorite graphic novelists. “Boxers & Saints” is among his best. These companion volumes tell the story of the Boxer Rebellion through the eyes of the characters Little Bao and Vibiana. Although they are on different sides of the struggle, their narratives mirror each other and their internal journeys weave together. For those seeking some historical fiction but with an approachable, illustrated style, Yang’s work is not to be missed.

LITERARY

“The Swimmers” by Julie Otsuka

“The Swimmers” is the newest release from critically acclaimed writer Julie Otsuka. Among her accolades, she has received the Guggenheim Fellowship and the Arts and Letters Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Experimental in form and craft, “The Swimmers” is about what happens to a group of recreational swimmers when a crack appears at the bottom of their pool, and about a woman named Alice.

Celebrate Arab American Heritage Month with great reads from the Library!

April is Arab American Heritage Month and UVA Librarians are celebrating by putting together some resources to help you explore literature, film, and poetry created by Arab Americans! Amy Hunsaker, Librarian for Music and Performing Arts, prepared the following list. Please direct research queries involving Arab American experiences, histories, and lives to Phil McEldowney, Librarian for Middle East and South Asia Studies.

Want to explore Arab American literature but don’t know where to start? UVA Library holds a substantial collection of Arab American fiction, poetry, and non-fiction. Here are some books to get you started.

“Modern Arab American Fiction: A Reader’s Guide” by Steven Salaita

“Modern Arab American Fiction: A Reader’s Guide” by Steven Salaita

A guide for people with little experience in this genre and who want to learn more about the writing traditions of Arab American fiction. The book provides an introduction to and critical examination of many works by notable Arab American writers, while exploring the cultural background of the writers’ countries of heritage — Lebanon, North Africa, Palestine, Iraq, and more. Short stories and poetry are provided in full with commentary for notable full-length novels.

“The Other Americans” by Laila Lalami

“The Other Americans” by Laila Lalami

Lalami has published notable works, including “The Moor’s Account,” which won multiple awards and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. The Other Americans is her latest novel, a murder mystery which cleverly uses multiple first-person perspectives to explore the relationships of within the Moroccan American Guerraoui family that finds itself at odds with its rural Southern California neighbors.

“The Beauty of Your Face” by Sahar Mustafah

“The Beauty of Your Face” by Sahar Mustafah

Trigger warning: vivid description of a school shooting.

A radicalized shooter has attacked a Muslim girl’s school where the daughter of Palestinian immigrants serves as principal. As the horror unfolds in the present, the author takes the reader to the past, showing the principal as a young Muslim girl in America, struggling to stay true to her family and heritage while fitting into an often belligerent American culture. These flashbacks prepare the reader for the protagonist’s dramatic confrontation with the shooter as she struggles to understand why he would commit this horrible crime.

“Out of Place: A Memoir” by Edward Said

“Out of Place: A Memoir” by Edward Said

A reading list of Arab American authors would be incomplete without a work by intellectual scholar and leading advocate for Palestinian rights, Edward Said, who is known for his groundbreaking works “Orientalism” and “Culture and Imperialism.” In his memoir, Said explores his “otherness” as a person living in exile in various countries throughout his life, and lays bare the plight of Palestinian refugees who were ousted from their homeland regardless of wealth or stature. While Said’s intellectual works are lofty academic discourses, his memoir looks inward as he reflects on his own remarkable life.

Looking for more?

If you are looking for a more comprehensive list of literature to explore, The National Endowment for the Humanities maintains Muslim Journeys, a virtual bookshelf that focuses on Muslim culture and literature as part of their Bridging Cultures Bookshelf.

Additionally, BackStory, a podcast series supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and Virginia Humanities, provides an in-depth look at America’s relationship with Islam in a variety of segments produced in 2015.

And finally, check out the Ottoman History Podcast created by UVA History professor Chris Gratien, which sustains and supports academic discussion about Turkey and the Middle East.

Discover a forgotten chapter of women’s history in “Black Women’s Suffrage”

The movement to extend voting rights to African American men after the Civil War was immediately accompanied by a push to expand the goal to include women. However, it would take both Black and white women over half a century more of struggle to finally secure the right to vote with passage of the 19th Amendment. The Black Women’s Suffrage resource explores the twin burden faced by Black women in the suffragist movement who not only fought against gender bias that denied women the right to vote, but against racism which denied people of color even the most basic of human rights. It was a fight for civil rights, a fight against lynching, and often a fight against the racism directed at them from within the Suffrage Movement itself.

Black Women’s Suffrage draws together primary resources from libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions, providing documentation on women such as Mary Church Terrell and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, whose critical role at the forefront of the campaign for women’s rights are too often forgotten.

You can search the database in a variety of ways; and the links will lead you to multiple primary documents of the era.

Timeline

Follow events from the founding of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833 through 2013 when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a key component of the Voting Rights Act. See racial fault lines develop within the movement early on, as when Elizabeth Cady Stanton used racist language to object to the extension of the franchise to Black men and not to women. In 1865 she wrote, “In fact, it is better to be the slave of an educated white man, than of a degraded, ignorant Black one.”

Key Figures

Learn how Charlotte Vandine Forten and her three daughters helped found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, the first biracial organization of female abolitionists in the United States. Learn also how in the 1960s civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer overcame being fired from her job and having shots fired into the house where she was staying to register to vote in Mississippi. For her continued activism, Hamer was arrested and severely beaten, suffering injuries from which she never fully recovered.

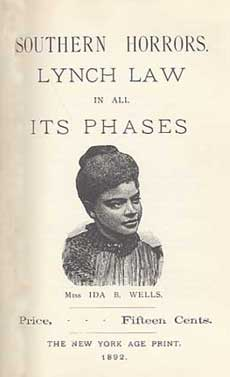

Collections

Study featured historical collections such as the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Papers, including the autobiography, diaries, articles, speeches, accounts, newspaper clippings, and photographs of the teacher, journalist, and anti-lynching activist. Wells-Barnett was born enslaved in 1862 and was educated at Shaw University (now Rust College) and Fisk University. As a student in 1884, she fiercely resisted being put off a train for refusing to comply with Jim Crow seating and won a small settlement. In 1892, when three of her acquaintances who worked in a successful Black-owned grocery were lynched, Wells-Barnett’s investigations found that not only were accusations against victims always false, lynching was essentially a tool used to preserve white supremacy and restrict upward mobility of African Americans. She believed that enfranchisement was key to ending lynching and winning civil rights and was a passionate proponent of Black women’s suffrage. In 2020, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize special citation “[f]or her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.”

Other primary source sets from the Digital Public Library of America cover topics such as:

- The American Abolitionist Movement

- Ida B. Wells and Anti-Lynching Activism

- Women’s Suffrage: Campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment

- Fannie Lou Hamer and the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi

- The Black Power Movement

- The Equal Rights Amendment

You can find this and other resources on women’s history in the Library’s A-Z Databases list!

Browse by category

Browse by date

- November 2018 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- November 2019 (1)

- January 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (2)

- October 2021 (1)

- November 2021 (1)

- January 2022 (4)

- February 2022 (2)

- March 2022 (2)

- April 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (3)

- August 2022 (1)

- September 2022 (2)

- November 2022 (4)

- December 2022 (3)

- January 2023 (6)

- February 2023 (9)

- March 2023 (11)

- April 2023 (6)

- May 2023 (4)

- June 2023 (3)

- July 2023 (1)

- August 2023 (3)

- September 2023 (5)

- October 2023 (7)

- November 2023 (3)

- December 2023 (5)

- January 2024 (4)

- February 2024 (8)

- March 2024 (2)

- April 2024 (6)

- May 2024 (4)

- June 2024 (1)

- July 2024 (2)