The University of Virginia Library’s major new exhibition: “Their World As Big As They Made It: Looking Back at the Harlem Renaissance” is in full swing. Located in the Main Gallery of the Harrison Institute and Small Special Collections Library, the exhibition opened in September to a packed house and has garnered attention for featuring some of “the Harlem Renaissance’s most popular magazines, manuscripts and original dust jackets of major works, and even some of the period’s fashions.”

The exhibition’s title is inspired by the Georgia Douglas Johnson poem, “Your World,” in which she looks back at the creativity of the Harlem Renaissance, acknowledges the hardships of being an emerging artist, and beckons a new generation of Black artists, writers, poets, publishers, and other creatives with the line: “Your world is as big as you make it.”

In that spirit, Library curators put out a call this past summer for contemporary artists to create works that would explore or respond to poems by Harlem Renaissance authors (curators selected nine poems for artists to choose from by writers including Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Helene Johnson, and of course, Georgia Douglas Johnson). This project, titled “As Big as We Make It!” was sponsored by a grant from the UVA Arts Council.

The selection committee members – Tamika L. Carey, UVA Associate Professor of English; MaKshya Tolbert, a third-year MFA student at UVA; and Maurice Wallace, a professor of English at Rutgers University-New Brunswick – selected five contemporary artists with connections to UVA and Charlottesville to showcase their work in the exhibition. Read more about them below.

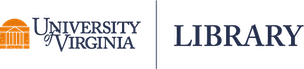

Abreale Hopkins, “Above the Heights”

Abreale Hopkins hails from Maryland and now resides in Brooklyn, New York. She received her B.A. from UVA in African American Studies and painting. Hopkins’ work has been shown at the Bridge Progressive Arts Initiative, Ruffin Gallery, and in private collections.

Her painting, “Above the Heights,” is paired with Arna Bontemps’ 1924 poem “Hope.” In her artist statement, Hopkins writes: “Arna Bontemps describes hopelessness as an environment with an all-consuming, daunting energy that weighs heavily on one’s chest. This painting is a display of that purgatory filled by stillness, melancholy, and despair. Shades of grey build upon each other to create a clouded abyss that extends further away as you look. Bontemps reminds us that hope both strikes through our lives with a ferociousness that calls for action, and exists as a quiet idea waiting to catch our attention. … Hope flashes from above, tearing through the seemingly never-ending abyss. The rip running through the canvas is a physical depiction of hopelessness’ impermanence and fragility. The tear’s assertiveness forces your eyes and mind out of the haze, urging you to imagine a different existence.”

Tobiah Mundt, “Of Rivers”

Tobiah Mundt is a self-taught fiber artist from Houston, Texas. She studied architecture at Howard University and eventually left the field of architecture for sculpture. She uses rug tufting, wet felting, and needle felting techniques to sculpt abstract and figurative pieces centered on ancestry and symbolism. A New City Arts Initiative Fellow and former Artist Residence at the Bridge PAI in Charlottesville, her work has been exhibited in Texas, Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., and is in private and corporate collections locally and nationally.

Mundt’s tufted and needle-felted layered tapestry, “Of Rivers” connects with and responds to the poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” by Langston Hughes. Mundt writes: “The tapestry illustrates African American lineage and connection to the world through the four great rivers mentioned in Hughes’ poem. It further represents the African American’s claim to a future place in the world. … The main image on the tapestry is a black hand and forearm in the style of a linocut. The lines of the Nile, Congo, Euphrates, and Mississippi rivers are drawn with wool from the bottom of the forearm onto the palm and out through the fingertips to the top right of the tapestry. The top right of the tapestry is orange-red to represent a bright African American future. The four corners of the piece tell abstract stories of an African American past, present, and futures.”

Valencia Robin, “Dear Georgia”

Valencia Robin’s interdisciplinary practice includes poetry, painting, and sculpture. The recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, the Emily Clark Balch Prize, a Margaret Towsley Fellowship, a King-Chavez-Parks Fellowship, as well as fellowships from Cave Canem and the Furious Flower Poetry Center, she holds an M.F.A. in art & design from the University of Michigan and an M.F.A. in creative writing from UVA. Her work has been exhibited nationally and includes a two-person show at Charlottesville’s New City Arts and a solo show at Second Street Gallery. She currently lives and teaches in Johnson City, Tennessee.

Robin’s painting “Dear Georgia” is inspired by Georgia Douglas Johnson’s poem “Calling Dreams.” Robin writes: “My paintings are visual poems, metaphors for capturing my inter- actions with myself and the world. In this sense, I’m both an abstract and representational painter. Like a poem, they reach for the ineffable, try to make it legible.”

Lisa Woolfork, “Three Dark Girls, Loved”

Sewing and quilting are powerful tools for Black resistance, recreation, and rest, as well as storytelling and social justice. As the founder of Black Women Stitch, “the sewing group where Black lives matter,” and the host/producer of Stitch Please, a weekly audio podcast that centers Black women, girls, and femmes in sewing, Lisa Woolfork is committed to using her art practice and social platforms to foster greater understanding, creative expression, liberation, and connection in our communities.

In her artist statement Woolfork writes: “Three abstract figures occupy the center of the design and are superimposed by appliqué on top of a photorealistic fabric foundation of the same image. The quilt border is a textile adaptation in honor of Zora Neale Hurston, as seen in the print’s use of notebook and ledger paper as well as in the bounding white lines arcing over organic circles. This line refers to a sentence from Hurston’s autobiography, where her mother encouraged her to “Jump at the sun.” The piece engages with the first four lines of Gwendolyn Bennett’s poem, “To a Dark Girl.” The quilted scene freezes the girls in a moment prior to awareness of anti-Blackness. It is a moment in time when they were three dark girls, loved. The image is a childhood Polaroid of myself with my sisters wearing dresses made by our grandmother. I am delighted to bring this cherished memory to this exhibit.”

Kemi Layeni, “To Be A Black Girl”

Kemi Layeni is an artist, writer, educator, and M.F.A. Candidate at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts Graduate Film Program. She works in the mediums of film, photography, and installation art. Her work explores the intersections of history and its burden on the present, Black womanhood, and the experiences of Black people throughout the diaspora. When Kemi is not working on her art, she spends her time working with teenagers in her school and community in performing arts and writing.

Of her multimedia piece, Layeni writes: “In Gwendolyn Bennett’s “To a Dark Girl,” the speaker of the poem’s purpose is to uplift Black girls and women. This piece incorporates voiceover, music, and photos of myself, the artist, from my childhood to adolescence. I chose to start and end with photos of my mother and I to mirror the same relationship of the speaker of the poem and their audience. I chose photos from my adolescence, a time where I was deeply insecure and convinced I was anything but valuable and beautiful, and juxtaposed them with the poem. The piece goes from an imagined mother speaking to a daughter with the words of the poem, to that same daughter speaking to herself, while exploring Black girlhood.”

To see these works in person, visit the main gallery of the Special Collections Library, open weekdays and Saturday afternoons. Or attend our Final Friday event on April 26, 2024, for an open house-style celebration featuring gallery talks by exhibition curators.